THE PROBLEM OF MEANING IN FOLKLIFE

"The term [Folklore]" writes Dorson, "caught on and proved its

value in defining a new area of knowledge and subject of inquiry; but it also

caused confusion and controversy" (1972 : 1), as folklore both to the layman

ad to the academician suggests "wrongness, fantasy and distortion" (Ibid).

This wrongness and distortion has, after a century and half's illustrious history

of the discipline, eased a little but not vanished completely. Besides other outside

factors, it seems there certainly are strong inside weaknesses, probably inherent

in folklore theory, responsible on the one hand, for this continuation of wrongness

and distortion and on the other, for the lag one notices in folklore theory in

general. In other words, the germs of these inside weaknesses might have originated

in the past when theoretical discourse in folklore was at its beginning; but the

strength of these weaknesses has been durable so much so that it has thwarted

even the theoretical advancement of current folkloristics.

Our endeavour

in this brief study shall be to review the failures and successes of folklore

theory (or theories)![]() 1 in the context of its historical growth and development. After reviewing the

major theoretical prospectives, we shall test a folktale, rather a fairy tale,

placing it in the context of this theoretical review.

1 in the context of its historical growth and development. After reviewing the

major theoretical prospectives, we shall test a folktale, rather a fairy tale,

placing it in the context of this theoretical review.

The data -- a single

folktale -- selected for exemplification of this kind of review, should not be

construed as a weakness in the argument. In fact there is a definite theoretical

constraint on this choice and should, therefore, be treated as a basic weakness

in the folklore theory itself rather than in our argument, for it is well known

that almost all folklore theories emerged as a result of studying the traditional

tale![]() 2.

It is only recently that attempts to extend the scope of these tale-cut theories

to other equally important genres of folklore have been made

2.

It is only recently that attempts to extend the scope of these tale-cut theories

to other equally important genres of folklore have been made![]() 3.

3.

As is well known, the interest of the Grimm brothers in folklore was, for

sometime, subordinate to their linguistic (philological) investigations (which,

strictly speaking, has not concerned itself with the problems of meaning). Even

after the release from this subordination, the main concern of the Grimmian (particularly

Jacobian) effort, in quite conformity with the philological tradition of the times,

was to collect parallels and, if conditions permitted, to try reconstructions.

This demanded a reasonable collection of data and somehow tale, particularly the

rich and fascinating fairy tale, attracted the keen eye of the Grimms and the

result was that the philologically inspired reconstructional effort was, in due

course, drowned in the massive collection of Germanic tales. The Grimms finally

ended up as the greatest collectors of folktales. Obviously no serious attempt

was ever made by them towards finding the meaning in folklore. This, as said,

was due to the fact that the theoretical bias the Grimms inherited was not concerned

about meaning![]() 4.

4.

TOP

THE MALADY OF LANGUAGE

However, the efforts of the Grimm brothers laid down the foundations of a new

discipline and certainly a theoretical framework, however weak it might have been,

which eventually was picked up, besides other scholars, by Max Mu_ller and his

European contemporaries. Max Mu_ller did not drastically alter the Grimm's methodology;

he had great respect for the philological school. But he very soon realized that

the data language experts handle and folklorists attempt to interpret, may share

certain formal aspects; but these are basically different, having entirely different

functional objectives. These and other theoretical constraints, put by the nature

of the data itself, inspired Max Mu_ller to add folkloristic dimensions to the

philological thought in an attempt to conform it to the requirements of folklore

items, particularly myths, and also to answer the question of meaning which was

as central to the data he was investigating as it was to his solar mythology theory.

Therefore, forced by the pressures of the data Max Mu_ller extended the scope

of the philological theory and took it beyond the reconstructional objective into

the realm of meaning. in other words, keeping in view the aims of Max Mu_llerian

search, his model began where the philological model ended.

As is well

known, the philological circles of Max Mu_llerian days (or even the historical

linguistics of the present times) stopped their effort once the proto (*= which

could, perhaps, never be attested) form of a linguistic element was established.

No attempt whatsoever was made, then, to know the origin of the proto form, as

that would lead to the fundamental questions regarding the origin of language

itself -- an area which synchronic linguistics does not consider its main domain![]() 5.

The methodology philologists followed permitted to avoid questions of this nature.

But folklore presented entirely different problems. Once the philological model

was fitted on a folkloric form, its "proto" or known "original"

form established; unlike a philologist, folklorist's search did not end here.

He was in fact immediately confronted with even a harder question: what is the

meaning of the original form? Here ended his parallelism with the philologists

whose method did not guide him beyond this point. The seeming unreality and fantasy

one notices on the surface of meaningful folklore items particularly myths and

tales, made the investigations in folkloristics more meaning oriented than philology.

5.

The methodology philologists followed permitted to avoid questions of this nature.

But folklore presented entirely different problems. Once the philological model

was fitted on a folkloric form, its "proto" or known "original"

form established; unlike a philologist, folklorist's search did not end here.

He was in fact immediately confronted with even a harder question: what is the

meaning of the original form? Here ended his parallelism with the philologists

whose method did not guide him beyond this point. The seeming unreality and fantasy

one notices on the surface of meaningful folklore items particularly myths and

tales, made the investigations in folkloristics more meaning oriented than philology.

After having reconstructed the proto form say, [k] of Dravidian [c], a philologist or a linguist can satisfy himself and stop here (unless, of course, he is forced into the problems of foundations of language, psycho-linguistics, or the philosophy of language which, however, as we are led to believe, remain outside the domain of linguistic proper); but on the other hand, having somehow reconstructed the original Indo-European (or proto) form of the myth of Zeus or Indra, empirically speaking, a comparative methodologist does not feel satisfied and is, therefore, by the dictates of the data itself, bound to cross to the other realm: the realm of meaning.

That Max Mu_ller efforts to decipher meaning in folklore items, as is true of many folklore scholars of his times and even today, was, therefore, not the result of his own choice, but the constrains imposed by the data he was investigating and the influence of the residual questions philological theory had left unanswered. Os it is not without reasons to find Max Mu_ller, besides concentrating on the aspect of meaning in folklore, very frequently indulging in the philosophical exercise of finding an answer to the question of origin of language itself.

That Max Mu_ller saw the death of his solar mythology

theory, nourished and nurtured so fondly by him, in his own life time![]() 6,

shows not only the weaknesses of his theoretical base; but also the dangers folklore

theory poses when the question of meaning comes in.

6,

shows not only the weaknesses of his theoretical base; but also the dangers folklore

theory poses when the question of meaning comes in.

TOP

MIGRATION AND MEANING

Theodore Benfey, primarily

an Indologist like Max Mu_ller, skillfully avoided the pitfalls of the controversial

question of meaning in folklore, and centered his attention instead on the problem

of diffusion and tale migration. Benfey in a way became the source of a forceful

later trend, which developed quite parallel but slowly, to the rapid growth of

modern linguistics, both in philosophy and methodology and methodological field

of folklore scholarship. This trend bypassed the Max Mu_llerian effort of tracing

the meaning in folklore items and stuck to the notion of "origin", "Ur"

or "proto" forms and their dissemination as championed by early philologists.

However, Benfey's contribution over the early philologists (and folklorists who

followed their methods) was that folklorists could now explain similarity of their

data (again folktales) cross-culturally by the notion of migrational transmission

or the transmission of borrowing, besides genetic relations. This virtually meant,

as historical reconstructionalists and philologists had done earlier in the case

of human speeches, particularly lexical items; emphasis on comparative method

too rather than complete dependence on "internal reconstruction" method

which, however, was explainable only by genetic relations. In other words, Benfey

added one more, and historically important, dimension to the theories of the early

nineteenth century scholarship: that similarities of folklore items across continents

can be explained by recourse to historical forces such as migration and borrowing.

Indeed an excellent theoretical perspective which still holds good. But most of

us know, this theoretical contribution of Benfey was a natural biproduct of a

larger theoretical bias; which, however, was never proved![]() 7.

That folktales and other cultural artifacts in different historical unrelated

cultures could arise polygenetically (independent of each other's influence) was

something Benfey and his contemporaries could not think of. This concept of polygenesis,

by and large the most accepted concept for all kinds of theoretical development

of the current folklore scholarship, was the given of British Anthropological

School led by Tylor and Lang

7.

That folktales and other cultural artifacts in different historical unrelated

cultures could arise polygenetically (independent of each other's influence) was

something Benfey and his contemporaries could not think of. This concept of polygenesis,

by and large the most accepted concept for all kinds of theoretical development

of the current folklore scholarship, was the given of British Anthropological

School led by Tylor and Lang![]() 8

who very successfully pulled down the deteriorating remnants of Max Mu_ller's

and Benfey's atomistic edifice and blurred their thoughts once and for all.

8

who very successfully pulled down the deteriorating remnants of Max Mu_ller's

and Benfey's atomistic edifice and blurred their thoughts once and for all.

Benfey's

contributions to folkloristics cannot be denied even when it came as a biproduct

of his original theory not widely accepted. However, what is important here is

the fact that even these contributions ignored meaning -- the most important aspect

of folklore studies. In fact, Benfey opened new vistas for the reconstrucitonalist

- atomistic attitudes and inspired formalistic studies evidenced by the works

of the scholars following historical geographical or Finnish methods and Russian

formalistic structural theory![]() 9.

9.

TOP

THE FINNISH METHOD

Too much emphasis on form as the sole criterion for achieving the object of tracing

the original form and travel routes of a tale or any other item of folklore reduced

this method to mere statistical abstractions -- an attribute of a method rather

than a theory![]() 10.

Therefore, Finnish methods did not offer any altered or new theoretical perspective

except excellent applicational attributes of statistics and symbolic abstractions

by which the age old concept of historically reconstructing the "archetype"

or "Ur form" could now be sustained by these mathematical abstractions.

The method these scholars (especially Kaarle Krohn, C.W. von Sydow and Axel Olrik)

10.

Therefore, Finnish methods did not offer any altered or new theoretical perspective

except excellent applicational attributes of statistics and symbolic abstractions

by which the age old concept of historically reconstructing the "archetype"

or "Ur form" could now be sustained by these mathematical abstractions.

The method these scholars (especially Kaarle Krohn, C.W. von Sydow and Axel Olrik)![]() 11 adapted were, in short, to reduce a particular tale more or less to a statistical

abstraction by breaking it into traits and subtraits (sort of "motifs")

11 adapted were, in short, to reduce a particular tale more or less to a statistical

abstraction by breaking it into traits and subtraits (sort of "motifs")

![]() 12

after all its possible variants or versions

12

after all its possible variants or versions![]() 13

are collected, assembled and arranged. Then the hypothetical archetype of each

trait is established and thus "a projected list of archetypal traits is put

together as a possible basic type or the archetype of the whole tale"

13

are collected, assembled and arranged. Then the hypothetical archetype of each

trait is established and thus "a projected list of archetypal traits is put

together as a possible basic type or the archetype of the whole tale"![]() 14

which may or may not correspond to even one actual recorded version of the tale

in the initial corpus. Scholars who follow the Finnish methods eschew the question

of meaning and also the question of the ultimate origin of the item or items they

study. The inadequacy of the methodological tools prevents them from going beyond

the recorded versions. For instance, if a given culture possesses a history of

say hundred years of recording, printing, etc., of its folklores or songs, then

according to this methodology, the "proto" or the original reconstructed

form of any given item of folklore of this culture cannot go beyond hundred years,

both in its history and form, although we know that the item did exist in the

culture before hundred years as well; otherwise it is not logically possible to

think of its first version. One can again see the procedural hierarchy, scholars

following Finnish methods adapted, was very close to the philosophy of philologists

(ignoring the meaning, considering only recorded [even only written] items, using

the logic of frequency, formulating laws by ignoring cultural circumstances and

above all attempting to squeeze out everything possible out of the text and text

alone)

14

which may or may not correspond to even one actual recorded version of the tale

in the initial corpus. Scholars who follow the Finnish methods eschew the question

of meaning and also the question of the ultimate origin of the item or items they

study. The inadequacy of the methodological tools prevents them from going beyond

the recorded versions. For instance, if a given culture possesses a history of

say hundred years of recording, printing, etc., of its folklores or songs, then

according to this methodology, the "proto" or the original reconstructed

form of any given item of folklore of this culture cannot go beyond hundred years,

both in its history and form, although we know that the item did exist in the

culture before hundred years as well; otherwise it is not logically possible to

think of its first version. One can again see the procedural hierarchy, scholars

following Finnish methods adapted, was very close to the philosophy of philologists

(ignoring the meaning, considering only recorded [even only written] items, using

the logic of frequency, formulating laws by ignoring cultural circumstances and

above all attempting to squeeze out everything possible out of the text and text

alone) ![]() 15.

15.

Whatever the other outcome, Finnish methods introduced what I would like

to term "refineness" in folklore scholarship. It certainly emphasized

mathematical accuracy in analytical procedures thus minimizing the chances of

imaginative speculation. Besides other good things, this inspired the creation

of valuable folklore lexicons such as the Type Index and the Motif Index![]() 16

and also opened up the possibilities of the use of electronic computer technology

in folklore studies

16

and also opened up the possibilities of the use of electronic computer technology

in folklore studies![]() 17.

More than any other group, modern structuralists seem to have borrowed, at least

the symbolism and the language of analysis, from the Finnish methods despite the

fact that structuralism in folklore was born as a reaction to Finnish methodology

and diachronic studies

17.

More than any other group, modern structuralists seem to have borrowed, at least

the symbolism and the language of analysis, from the Finnish methods despite the

fact that structuralism in folklore was born as a reaction to Finnish methodology

and diachronic studies![]() 18.

I have delved into these and related problems elsewhere

18.

I have delved into these and related problems elsewhere![]() 19.

19.

TOP

THE SYNTAGMATIC APPROACH

As is well known, structuralism in folklore was born out of Russian formalist

thought. Vladimir Propp who was one of the major proponents, although not militantly

so, of Russian formalist thought during its short period of development (from

about 1915 to 1930) became the first structural folklorist with the publication

of his famous Morfologia skázki (1928) [Morphology of the Folktale] (1958)![]() 20. Propp's work was published in 1928, at a time when formalist school was at

the peak of its crisis -- officially condemned from within and with no communication

with the outside world. Threatened by these crisis, Propp himself had to adandon

formalism and morphological analysis in order to devote himself to historical

and comparative research on the relationship between oral literature and myth,

rites and institutions. However, the message of the Russian formalist school was

not to be lost. In Europe the Prague Linguistic Circle first organized and disseminated

it and in about 1940, the personal influence and teachings of Roman Jacobson brought

it to the United States where it did flourish for quite some time.

20. Propp's work was published in 1928, at a time when formalist school was at

the peak of its crisis -- officially condemned from within and with no communication

with the outside world. Threatened by these crisis, Propp himself had to adandon

formalism and morphological analysis in order to devote himself to historical

and comparative research on the relationship between oral literature and myth,

rites and institutions. However, the message of the Russian formalist school was

not to be lost. In Europe the Prague Linguistic Circle first organized and disseminated

it and in about 1940, the personal influence and teachings of Roman Jacobson brought

it to the United States where it did flourish for quite some time.

Propp's

method of measuring the morphological elements of fairy tales and ignoring the

content and context can be compared to that brand of linguistic structuralism

which thrives on formalistic thought and ignores semantics not because it deserves

to be ignored as they seem to claim; but because the brand's tools lack the sharpness

of even exploring this vital area. Prop being guided by this brand of linguistic

structuralism paid attention exclusively to the rules which govern the construction

of statements forgetting that formalism loses sight of the fact that no language

exists in which vocabulary can be deduced from the syntax. The study of any linguistic

system requires the combined efforts of the grammarian and philologist. "Thus

for oral tradition, morphology is sterile unless ethnographic observation, direct

or indirect comes to fertilize it. To imagine, as Propp does, that two tasks can

be separated -- first to undertake the grammar and to postpone the lexicon till

a later date -- is to condemn oneself to never producing more than a bloodless

grammar, and a lexicon where anecdotes take the place of definitions![]() 21".

When all is said to done, neither one nor the other would fulfil its task. Therefore,

"Propp is not torn, as he imagines, between the demands of synchrony and

diachrony: it is not the past that he lacks, but the context"

21".

When all is said to done, neither one nor the other would fulfil its task. Therefore,

"Propp is not torn, as he imagines, between the demands of synchrony and

diachrony: it is not the past that he lacks, but the context"![]() 22.

Propp's formalist dichotomy which distinguishes between form and content defining

them antithetically, is not imposed by the true nature of things, but by the accidental

choice he has made of a realm where only form remains while content is abolished.

This explains Propp's reluctance to work on the structure of myths. In short,

Propp's analysis tells us very clearly about the morphology of tales, the morphological

combinations construed as building blocks of tales (like the syntax rules in languages),

their finite nature and the conditions under which these operate. It also tells

us about the universality of folktale structure, of these building blocks which

make the creation of folktales possible. But it does not tell us why tales are

created in the first place; what functions they perform in a given society; why

these building blocks get grouped and regrouped in different tales; and finally

why is some cultures some building blocks seem more important than the others.

It was very honest of Alan Dundes, the first American folklorist to test Proppian

model cross-culturaly

22.

Propp's formalist dichotomy which distinguishes between form and content defining

them antithetically, is not imposed by the true nature of things, but by the accidental

choice he has made of a realm where only form remains while content is abolished.

This explains Propp's reluctance to work on the structure of myths. In short,

Propp's analysis tells us very clearly about the morphology of tales, the morphological

combinations construed as building blocks of tales (like the syntax rules in languages),

their finite nature and the conditions under which these operate. It also tells

us about the universality of folktale structure, of these building blocks which

make the creation of folktales possible. But it does not tell us why tales are

created in the first place; what functions they perform in a given society; why

these building blocks get grouped and regrouped in different tales; and finally

why is some cultures some building blocks seem more important than the others.

It was very honest of Alan Dundes, the first American folklorist to test Proppian

model cross-culturaly![]() 23,

to raise the question of meaning in respect of Propp's model very appropriately

in the "introduction" to the second edition of Propp's Morphology. Consider,

for example, his following remarks:

23,

to raise the question of meaning in respect of Propp's model very appropriately

in the "introduction" to the second edition of Propp's Morphology. Consider,

for example, his following remarks:

"The problem is Propp made no

attempt to relate his extraordinary morphology to Russian (or Indo-European) culture

as a whole. Clearly structural analysis is not an end in itself! Rather it is

a beginning, not an end. But the form must ultimately be related to the culture

or cultures in which it is found. In this sense, Propp's study is only a first

step, albeit a gaint one. For example, does not the fact that Propp's last function

is a wedding indicate that Russian fairy-tale structure has something to do with

marriage? Is the fairy tale a model of fantasy, to be sure, in which one begins

with an old nuclear family (Cf. Propp's typical initial situation "The members

of a family are enumerated" or Function 1, "one of the members of a

family is absent from home") and ends finally with the formation of a new

family (Function31, "The hero is married and ascends the throne")? Whether

it is so or not, there is no reason in theory why the syntagmatic structure if

folktales cannot be meaningfully related to other aspects of culture (such as

social structure)" (1968:xiii).

TOP

PARADIGM AND MEANING

Another brand of structural analysis

drawing inspiration from the French anthropological school and nourished by the

experiments of Claude Lévi-Strauss with Latin American Indian mythology

separates itself completely from formalism. Unlike formalism, scholars following

this type of structural analysis claim the discovery of mythological truth in

the unity of concrete and the abstract. Nor do they recognize any privileged value

in the latter. Form is defined in contrast to content, which lies outside of it.

However, they also claim that structure has no content. "It is content comprehended

in a logical organization which is conceived of as a property of reality"![]() 24.

These scholars, therefore, believe that Proppian analysis deals with form alone

whereas Lévi-Straussian structuralism takes care of both form and the content

simultaneously. Besides these, the other major differences between these two brands

of structural analyses are: Propp's morphological analysis is based on Russian

Fairy tales [märchen] while Lévi-Strauss is trying to uncover the

realm of the myths. Propp does not alter the "syntax" of the tale; in

other words, he attempts at deciphering its morphology (functions of the characters)

and the combinations as it is "given" by the informant (thus the name

"syntagmatic" structural analysis). Lévi-Strauss, on the other

hand, believes that the content of a myth comprehended in a logical organization

cannot, and should not, lie on the given structure and therefore needs "rearrangement"

by reducing the structural components to meaningful paradigms (hence the name

"paradigmatic" structural analysis).

24.

These scholars, therefore, believe that Proppian analysis deals with form alone

whereas Lévi-Straussian structuralism takes care of both form and the content

simultaneously. Besides these, the other major differences between these two brands

of structural analyses are: Propp's morphological analysis is based on Russian

Fairy tales [märchen] while Lévi-Strauss is trying to uncover the

realm of the myths. Propp does not alter the "syntax" of the tale; in

other words, he attempts at deciphering its morphology (functions of the characters)

and the combinations as it is "given" by the informant (thus the name

"syntagmatic" structural analysis). Lévi-Strauss, on the other

hand, believes that the content of a myth comprehended in a logical organization

cannot, and should not, lie on the given structure and therefore needs "rearrangement"

by reducing the structural components to meaningful paradigms (hence the name

"paradigmatic" structural analysis).

Lévi-Strauss draws heavily upon the linguistic theory of de Saussure, Trobetzkoy and Jacobson. He also borrows concepts from Freud and Gestalt in psychology, Rousseau, Durkheim, Mauss and Marx in anthropology, Kant and again Rousseau in philosophy and von Neumann, Wiener and Shannon in cybernetics. He sees myth as a language of higher level trying to resolve oppositions. These oppositions, binary in nature, are sometimes resolved by replacements or remain unresolved. Sometimes these might also lead to a chain of similar oppositions being the transformations of basic set of oppositions. This being so, one can very well see that this brand of Lévi-Straussian structural analysis deals with meaning; but the method conceives meaning as a logical formula based on polarities which it claims to decipher. Therefore, Lévi-Strauss' methodology in the final analysis, is a pirori formula which he tries to fit on all myths around the world.

Lévi-Strauss' this kind of epistemological approach is based on the hypothesized existence of an unconscious meaning of cultural phenomena. Since cultural meaning, according to Lévi-Strauss, remains hidden, therefore, empiricist methodology of immediate and spontaneous evidence fails to decipher it. This clearly shows that Lévi-Strauss is more concerned about the unconscious rather than conscious in cultures so much so that scholars begin to ask if Lévi-Straussian "polarities are in fact bonafide structural distinctions, they represent the structure of the universe depicted in a folktale or myth, but they do not represent the compositional structure of the folktale or myth narrative" (Dundes, 1971 : 172).

Lévi-Strauss' firm belief in Fruedian concepts that "genuine meaning lies behind the apparent one"; that "no meaning has to be accepted at its face value"; that the "true meaning… is not that of which men are aware"; and that "conscious data are always erroneous or illusory" clearly shows that he looks at conscious meaning as something which is not genuine and hence illusory. In an attempt to make the similarities and differences very clear between Freud and Lévi-Strauss, it is interesting to quote Fenichel, one of the authoritative interpreters of Freud. He explicitly says, "nor is it true that everything unconscious s the 'real motor' of the mind, and everything conscious merely a relatively unimportant side issue" (1945 : 15).

Therefore, as a departure

from Propp's formal methodology, Lévi-Strauss' structuralism does deal

with meaning, but with unconscious hidden meaning, which more or less seems to

him same across the continents. Lévi-Strauss, therefore, tell us, perhaps,

how myths are created at the unconscious level, but it does not tell us why they

are created, how they survive, and more importantly, are perpetuated functionally

irrespective of the changes that have occurred to mankind. Lévi-Strauss'

formulations have certainly added a new dimension to folkloristic research: it

has focused the attention of scholars on the structural universals in folklore;

and also enhanced the value of psychological investigations into the depths of

human mind or more appropriately "savage" mind![]() 25.

But the meaning in folklore, whether conscious or unconscious, still remains the

most important challenge modern folkloristics faces.

25.

But the meaning in folklore, whether conscious or unconscious, still remains the

most important challenge modern folkloristics faces.

TOP

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERPRETATIONS AND MEANING

We postponed a short review of psychoanalytical methods deliberately. It ought

to have chronologically occurred immediately after Finnish methods. The reason

to take it up after having commented upon Lévi-Strauss' theory is obvious:

both have much in common as we have seen in the above discussion; and since the

main focuss of this brief study in on the problem of theory and meaning, it seems

most appropriate to review these two important theoretical devices at one place

in a logical rather than chronological manner as both are concerned about meaning.

Psychoanalytical school, as is well known, has been and still is, loaded

with sexual symbolism. This symbolism has gone so far that sometimes scholars

suspect a direct historical connection between the German celestial mythologists

and Austrian psychoanalytical folklorists who have borrowed the method of their

predecessors and simply changed the symbols![]() 26.

The revolutions which took place in the explorations of human mind with the writings

of Sigmund Frued, the father of modern psychoanalysis, and others, heavily influenced

the theoretical aspects of folkloristics. Psychoanalytical explorations were mainly

based on dreams and their dreamers. Since dreams are never meant to be understood

as conscious manifestations of dreamer's activity, they naturally pose problems

of interpretation. With the help of the dreamer, psychologists attempted at translating

the dreams from the unconscious fantasy to a conscious meaningful symbolic phenomenon.

Since folklore, particularly myth and folktale, also could not be understood when

related to objective reality, it was presumed, and thoughtfully so, that these

resemble dreams and need to be subjected to a similar analysis. However, there

were some basic differences. In the case of dreams no amount of psychology and

its methodology can be useful unless the dreamer too is psychoanalytically studied.

In fact, the sources of deciphering symbolic meaning in a dream lie in the personality

of a dreamer. Myth and folktale, particularly those which relate to past, also

need, then, to be examined with a knowledge of their makers. This argument, however,

valid it might look, poses some problems. Even if the knowledge of a myth maker

is available along with the myth for analysis, our analytical tools stop operating

when it is revealed to us that the status of this myth to its maker is not the

same as the dream to the dreamer. While the dream is a idiosyncratic expression

of an individual, the myth is backed by the psychology of the group, sometimes

the entire members of a culture or even a nation. The other problem is that a

narrator is really not a myth maker, and therefore, relating his personality to

the myth in the same manner as dream to the dreamer does not seem justificable

in view of the theoretical requirements. That both can be subjected to same theoretical

model seems highly doubtful. Therefore, it becomes imperative on the part of the

anthropologists and folklorists to relate the manifest and latent content of the

myth not only to its so-called "makers" or narrators but to the culture

as a whole. In fact for better results it is important to consider the culture

as the myth maker and relate the myth to all its manifestations -- even historical.

Complete dependence on text will neither fulfil the demands of psychoanalytical

theory nor permit us to know even a fraction of what all of us are trying to.

26.

The revolutions which took place in the explorations of human mind with the writings

of Sigmund Frued, the father of modern psychoanalysis, and others, heavily influenced

the theoretical aspects of folkloristics. Psychoanalytical explorations were mainly

based on dreams and their dreamers. Since dreams are never meant to be understood

as conscious manifestations of dreamer's activity, they naturally pose problems

of interpretation. With the help of the dreamer, psychologists attempted at translating

the dreams from the unconscious fantasy to a conscious meaningful symbolic phenomenon.

Since folklore, particularly myth and folktale, also could not be understood when

related to objective reality, it was presumed, and thoughtfully so, that these

resemble dreams and need to be subjected to a similar analysis. However, there

were some basic differences. In the case of dreams no amount of psychology and

its methodology can be useful unless the dreamer too is psychoanalytically studied.

In fact, the sources of deciphering symbolic meaning in a dream lie in the personality

of a dreamer. Myth and folktale, particularly those which relate to past, also

need, then, to be examined with a knowledge of their makers. This argument, however,

valid it might look, poses some problems. Even if the knowledge of a myth maker

is available along with the myth for analysis, our analytical tools stop operating

when it is revealed to us that the status of this myth to its maker is not the

same as the dream to the dreamer. While the dream is a idiosyncratic expression

of an individual, the myth is backed by the psychology of the group, sometimes

the entire members of a culture or even a nation. The other problem is that a

narrator is really not a myth maker, and therefore, relating his personality to

the myth in the same manner as dream to the dreamer does not seem justificable

in view of the theoretical requirements. That both can be subjected to same theoretical

model seems highly doubtful. Therefore, it becomes imperative on the part of the

anthropologists and folklorists to relate the manifest and latent content of the

myth not only to its so-called "makers" or narrators but to the culture

as a whole. In fact for better results it is important to consider the culture

as the myth maker and relate the myth to all its manifestations -- even historical.

Complete dependence on text will neither fulfil the demands of psychoanalytical

theory nor permit us to know even a fraction of what all of us are trying to.

TOP

THE GENRE AND THE PROBLEM

OF MEANING

Another problem which seems to have been ignored by scholars

following psychoanalytic methods, is that of genre. More often than not, scholars

have emphasized the fact that myths and folktales carry hidden messages found

on the latent and not on their manifest content. Same scholars seem to agree that

meaning in other genres such as proverbs, riddles, and many other forms of folklore

usually lies in the manifest content. This perhaps explains why myths and folktales

are subject to psychological analysis more often than proverbs, riddles and most

of the oral poetry. One wonders what functional qualities and cultural circumstances

have loaded myths and folktales with hidden symbolic meanings and left the other

forms without it? Is it due to the fact that myth and tale are really having hidden

meanings and as such require specific techniques to decipher them or it is simply

the weakness of folktale - myth - cut folklore theory unable to enfold other equally

important and meaningful genres. Even more surprising is the fact that scholars

on the one hand have already started discovering cultural meanings across genres,

and on the other hand, they don't want or cannot operate their tools across genres.

This also shows beyond doubt that not our general theoretical tools only are weak,

but out classificatory system and devices to ensure sound analytic categories

are equally inadequate![]() 27.

This is substantiated by the problems modern folkloristics faces in defining genres.

27.

This is substantiated by the problems modern folkloristics faces in defining genres.

Equally important, controversial though, is the problem of sexual symbolism employed traditionally as the main theoretical technique for justifying a sound psychological analysis. Sex has so much been championed in these methods that sometimes it seems as if it is being imposed from above rather than seen emerging out of the text or context or both. Even if the type of sexual symbolism employed by psychology inspired folklorists to understand the meaning in folklore is granted; one wonders why this kind of symbolism should be the beginning and the end of myth and tale (and similar form of narrative) and not of folksong, proverb, riddle or a ballad. Of course, sexuality, in symbolic form or without it, is noticeable in these genres as well; but the question is why is it manifest in the content of these forms, whereas in myth and tale it always, we are told, is latent. Are these generic differences or the weaknesses in folklore theory in general.

Another important problem with the sexual symbolism practised by folklorists following psychoanalytic techniques is that they usually do not believe in the hypothesis that an effort in the unification of latent and manifest content of the materials they investigate might logically be an acceptable answer to the problem of meaning in folklore. Rigid theoretical orientation, as we showed above while reviewing Lévi-Strauss' methods, does not seem to have permitted such scholars to even recognize the value of manifest content. It is precisely because of these theoretical notions that folklorists and anthropologists following psychoanalytic methods, tend to picture sexual anxiety as the source of all anxieties of a culture, which, however, seems as speculative as the generalizations they make ignoring the differences of sexual symbolic systems that exist in various cultures.

However, in spite of these and other drawbacks, psychoanalytic methods seem to be the only technique, however inadequate, which concerns itself with the meaning of folklore items. That structuralism, for its quest for meaning in folklore, also derives inspiration from psychology, needs hardly to be emphasized.

Our main concern,

as we outlines in the beginning of this brief study, was to outline the major

weaknesses in folklore theories as far as the meaning in folklore items is concerned.

This concern, as we are aware, has been central to the growth of folkloristics.

It is, in our opinion, this aspect which separates folklore from many other sciences,

where the concern for meaning may not be so compelling; and it is this aspect

which places folkloristics very close to many other disciplines such as history,

archaeology, literature, arts, etc., in which the meaning has always remained

paramount.

TOP

S?NYKIS?"R

: A CASE STUDY

The above review has shown us that among the current major

theoretical devices structural (particularly, Lévi-Straussian "paradigmatic"

analysis) and the psychoanalytical are the only two methods which concern themselves

with the aspect of meaning in folklore. Both have their own successes and failures,

as we have discussed above. We would not like to apply the structural (both Proppian

and Lévi-Straussian) and psychoanalytic methods to a popular Kashmiri folktale

(s?nykis?"r)![]() 28 in an attempt to (i) justify what we said in the review, particularly in respect

of these two theoretical devices and (ii) to pin-point the areas of residual elements

which, however, need clarifications. This we believe, should fulfil both the objectives:

to focuss the attention on the problem of theory and meaning and to indicate to

the ways in which this problem could probably be solved.

28 in an attempt to (i) justify what we said in the review, particularly in respect

of these two theoretical devices and (ii) to pin-point the areas of residual elements

which, however, need clarifications. This we believe, should fulfil both the objectives:

to focuss the attention on the problem of theory and meaning and to indicate to

the ways in which this problem could probably be solved.

The Tale : S?nykis?"r

A school-going brother is served food by his younger sister, S?nykis?"r. He finds a hair in his meal. This upsets him. Says he: "whosoever's hair is this she will be my wife". The mother, angry at her son's incestuous comment, scolds him by saying that the hair might be of his own sister or mother. The boy ignores his mother and repeats the comment. Annoyed, the sister leaves the home in disgust. She is given seven seeds by a holy man (faqi"r) which instantly grow into seven tall trees. She climbs the top of one tree. Her brother and father in an attempt to rescue her back home cut off the trees; but she jumps into the house of mother moon. She is asked by the moon to comb her hair daily without ever touching the centre of her skull (tsurikhod). Soon by chance she violates the interdiction. The moon loses her hair and S?nykis?"r is thrown down the sky. She falls into a crow's nest in deep woods who eventually adopts her as his child. Some time later, she is again discovered by her brother and parents. They try to allure her back home by reminding her of her colourful spinning wheel, the wedding dress, and beautiful dolls. But she refuses to go. Soon thereafter, the king, while on a hunting trip, finds her and both fall in love with each other. The king without waiting for the crow's consent, cuts off the tree and takes S?nykis?"r to his palace as his youngest seventh queen. Undecided whom to make the chief queen, the king proposes three tests (husking of paddy, decorating the palace, cooking the nicest dish) to the queens. With the help of the crow and her own cleverness, S?nykis?"r excels in all three tests and is finally selected as the chief queen and the other six are thrown out of the palace. Both live happily ever after.

In terms of Propp's model the tale seems to have the following sequence of functions which determines its structure:

initial situation

: a donor : D

interdiction : Ò test : E

violation : d help : F

villainy / lack : A (a) lack

departure : liquidation : K

Here ends the move but not the tale. The functions are repeated and the tale is lengthened and changed from a single move (xod) tale to a multi-move one. The repetitions are identical and occur twice besides the basic move which however has also the suffix function of "Wedding with throne" (W*). The design of these morphological combinations is as follows:

[a] Ò d A(a) DEFK/

Ò

d A(a) DEFK/

Ò d A(a) DEFK [W*]

This exercise of applying Propp's model to this single tale is not fruitless. On the contrary, it gives us a clear picture of the qualities of functions which form the structure of the tale. For instance, it tells us that the tale basically is a short, one move tale, but the repetitions have made it longer. It also tells us that the repetitions are identical. Obviously, this kind of analysis does not tell us anything about the meaning of the tale; but it does give us one clue, however insignificant; that if there is going to be any meaning in this tale, then, that is being, structurally speaking, repeated.

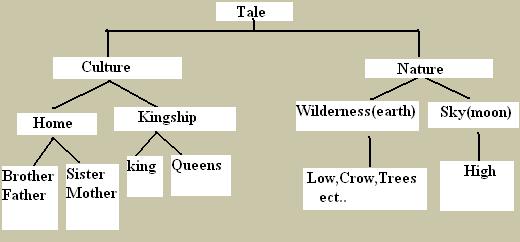

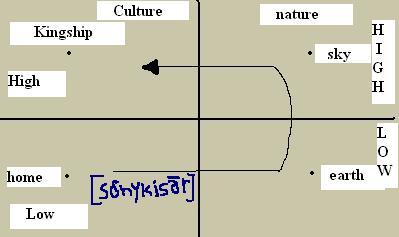

Let us turn the side and see how far the tale agrees with Lévi-Straussian methods. One of the ways (there certainly are other ways as well) of looking at this tale (ignoring the fact that Lévi-Strauss' theory grew out of myths) is to look at the oppositional paradigms. The tale clearly tries to show opposition between the nature and culture. This latent opposition gradually becomes manifest in the form of such oppositions as home and wilderness, male and female and high and low.

If one looks from the point of view of kinship systems and the oppositional messages they convey, one would not be surprised to find an identical oppositional phenomena occurring at the beginning and the end of the tale.

First part Sister

leaves

home because

the

brother

lacks wife.

Last Part queens

leave

the palace

because the

king has too

many of them

The logical message looks as if

excess of something creates as much disequilibrium as the lack of same thing would![]() 29.

In other words, a balanced home and society depends on following the established

social and kinship norms: Polygomy can be as distructive for both as would incest

- facts which hardly seem untrue in view of history and social structure of Kashmir

or even India. There is yet another way of looking at the structure of the tale:

it would seem as if S?nykis?"r is attempting to mediate between the two opposite

realms of culture and nature.

29.

In other words, a balanced home and society depends on following the established

social and kinship norms: Polygomy can be as distructive for both as would incest

- facts which hardly seem untrue in view of history and social structure of Kashmir

or even India. There is yet another way of looking at the structure of the tale:

it would seem as if S?nykis?"r is attempting to mediate between the two opposite

realms of culture and nature.

It will be worthwhile to postpone further comments on the above analysis till we have tried the psychoanalytic methods on this tale, for, as we shall see later, there will be many similarities in the outcome of both.

Psychoanalytically,

we find the tale pregnant with symbols of strong sexual connotations. It will

be most appropriate to divide the tale syntagmatically into basic episodes and

decipher symbolic meanings in each episode and then correlate all such meanings

into one holistic meaning. Following this line, we find this tale has three episodes;

structurally identical as evidenced by morphological analysis: (i) S?nykis?"r's

leaving her home up to jumping into the moon's house, (ii) her fall from the moon's

house up to cutting off the tree by king's men and (iii) her entering the palace

as the youngest queen, till the end. Let us take the first episode first. The

symbols we gather that can be interpreted psychologically are: hair in the rice

bowl, seeds, quick erection of trees, climb over the tops of trees, cutting off

the trees, combing or touching the central part (tsuri khod; lit. "hidden

hole") of mother moon and the instant fall. All these metaphors certainly

seem to represent disguised sexual anxieties and more often than not, sex inspired

anxieties of the kinship order. This part of the tale then begins with the threat

of incest leading suddenly, on the one hand, to its escape and on the other, gradually

ending up in female sexual fantasy. This is symbolically represented by such strong

sexual symbols as the quick erection of trees, S?nykis?"r's climb on every

tree-top (seven in all), entering moon![]() 30,

touching her "hidden hole" and the fall. Moreover, the cutting down

of trees here (and elsewhere also) suggest the disguised castration as a preventive

means for such fantasy, which, to be sure, even the mother figure moon also is

shown discouraging. In the second part of the tale, this fantasy seems to be re-established

by more symbolic expressions such as the fall, nest, spinning wheel, dolls, wedding

dress and again chopping off the tree. This part also introduces the father figure

crow representing the non-human world. The third part also having some symbols

denoting sexuality like husking of paddy, etc., nevertheless, seems symbolically

concerned with re-establishing the sound kinship norms temporarily threatened.

30,

touching her "hidden hole" and the fall. Moreover, the cutting down

of trees here (and elsewhere also) suggest the disguised castration as a preventive

means for such fantasy, which, to be sure, even the mother figure moon also is

shown discouraging. In the second part of the tale, this fantasy seems to be re-established

by more symbolic expressions such as the fall, nest, spinning wheel, dolls, wedding

dress and again chopping off the tree. This part also introduces the father figure

crow representing the non-human world. The third part also having some symbols

denoting sexuality like husking of paddy, etc., nevertheless, seems symbolically

concerned with re-establishing the sound kinship norms temporarily threatened.

If we sum up these fragments into a holistic meaning, we seem to be clearly dealing with a tale of female sexual fantasy (the title meaning "wondering around deep" also suggests this) followed by an indication of its control by various stabilizing cultural forces re-establishing the sound social norms and eventually channellising these "destructive" powers into constructive and lasting social stability. The human, non-human dichotomy also suggests firmly the re-establishment of social norms. For humans adhering to social norm is as important as being free from it for birds or animals. Those who attempt (be it in fantasy) to violate social norm are guilty of belonging to, or are forced into the world of non-humans (birds for instance) and live like them or with them.

That the tale expresses, by and large, a meaning similar to one we could get when examined structurally, justifies our postponement of the comment on Lévi-Strauss. If we compare the results of both these analyses now we find that in this tale, through the medium of a strong sexual fantasy (which, however, can also be explained independent of these relations in view of male chauvinism and the strong social control over the women in this culture particularly), human, non-human (or nature/culture) dichotomy emphasizes the importance of social structure and the disadvantages of reversed kinship order. The repetition in this theme should be viewed in terms of the structural repetition we noticed in the tale at the level of Proppian analysis.

So far we have only been depending on text; and we know it is important that the deciphered meaning of the text be, to some extent, substantiated by the contextual evidence as well. Without going into minute details, suffice it to say that this tale is considered an "inside tale" or a family tale. Observations have shown that the tale is repeatedly told to young girls, particularly unmarried girls, by elderly women in Kashmiri homes. This little contextual information tends to confirm whatever results we could achieve so far.

We have almost completed this brief study. To conclude the problem we raised in the beginning, it is clear now that given all these major theoretical devices, folklore items do not easily yield the kind of meaning on would expect. This is not only, as some would presume, due to the fact that most of the folklore items have gained or dropped some their meaningful elements in course of their travel, diffusion, and dissemination; but also due to the inadequacy of methodological tools we have been able to develop over the years. Even after the application of all (sometimes opposing) major methods if we fail to solve the problem of meaning of an item of folklore; one can sympathize with those trying to decipher everything within the framework of a single method.

The very position of folklore in the

cultural milieu shows its complex relationship with other cultural expressions.

Therefore, a subject which is, by its own nature, positioned in a highly complex

network of such relations, cannot escape complexities in its theoretical growth.

What folklore needs is serious interdisciplinary treatment; and of course, balanced

theories and balanced theoreticians.

TOP