At

our first meeting we solicited from one another a body of folktales on which we

could then concentrate analysis and interpretation. This initial collection of

tales exhibited a variety of traditional folkloristic themes: the ogress queen,

cruel in-laws, contests between spouses, rivalry between wives, the folklore of

objects like mirrors, the capture of women, pursuit, forgetfulness, and substitution.

The problem was to find a focus. Each story we told suggested new themes and new

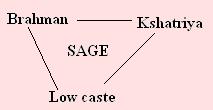

avenues to explore. Eventually we settled on a single idea: certain key positions

or social categories depicted in folktales, along with their transformations,

we then agreed to explore exchanges or movements of characters between any two

of the following positions: Brahman, Ks?atriya, low caste, and outsider/sage.

We considered each of the logical possibilities, in turn. The details are described

below.

Brahman> Low Caste, and Low Caste >Brahman

The first topic

discussed concerned Brahmans who become transformed through a folktale, into a

low caste character. One Shaivite story, told both in Kashmir and in South India

(Telugu, Tamil, Kannada) speaks of a Brahman names Cirutton?t?ar, who is put through

an ordeal by Shiva. This great god is described visiting his devotee in disguise.

Cirutton?t?ar, suspecting that his guest might be a god, offers to serve him anything

he requests. The god then asks that he slaughter his own son, cook him, and serve

up a dish of human flesh. Carrying out this horrible request makes the devotee

into a kind of outcaste, because of his involvement with a bloody (and terrifying)

sacrifice. In another Shaivite story Shiva uses a similar disguise, making a faithful

follower slice up a dead buffalo to serve his guest. The worshipper then suffers

a loss of status due to his work as a butcher. In one Tamil villupat?t?u (bow

song) a Brahman named Muttuppat?t?an, is said to fall in love with the daughters

of a low caste cobbler chieftan; the latter makes the suitor prove his eligibility

by his willingness to take up an untouchable cobbler's tasks; he has to cut up

a dead cow, skin it, and tan the hide. In all these stories, a Brahman willingly

becomes an untouchable by his own deeds, either done to show his love of god or

his love of a woman.

The reverse transformation, low caste >Brahman is illustrated by several South

Indian goddess stories where an untouchable marries a Brahman girl by trickery.

He takes on all the outward ways of a Brahman, but in the end does not get away

with this ruse. When such a deception is discovered by the man's Brahman wife,

she feels violated or defiled. Fury possesses her and she becomes a powerful goddess.

Another

example of the low caste >Brahman transformation is found in a story of Bangaladesh.

This folktale describes a bad Brahman who has a low caste servant named Ghughu.

Ghughu was staved, overworked and beaten until he died. On his deathbed he prayed

that he be reborn transformed into a Brahman. In his new life he becomes Farid,

a poor Brahman boy. In this condition he sought out his former master and became

his servant, insisting on the condition that he never be dismissed. One day, the

one-year-old son of this Brahman dirtied himself. The master therefore asked his

servant to wash the child in the river. Farid literally followed his master's

orders: he washed the child on a wooden platform as he would a piece of cloth.

Then he brought back a well-washed but dead infant to his master.

Another

time the Brahman master asked this servant to escort his wife to another village.

He gave Farid orders to protect her if the two were attacked by thieves, using

a Bengali word which could be mistaken for 'rape'. Sure enough, they were attacked

on the way, and the servant first saved the woman but then raped her in the jute

filed. The Brahman was bound by contract not to dismiss his servant. So he complained

instead to the king. The king sentenced the servant to be burned on the riverbank.

Just before the funeral pyre was lit Shiva appeared and asked the Brahman master

to show mercy and take his servant back. The Brahman did. One day, tormented by

this man, the master used a desperate Bengali phrase: "Farid, why don't you

take my ears (literally 'find my ears and cut them off') and leave me along?"

Farid, as usual, followed his master's instructions literally and brutally. He

at once cut off the ears of the Brahman, and while leaving said to him, "ghughu

dekhechoo kintu farid dakoni." From these words one gets a proverb which

says: "You've seen the dove, but you haven't seen the snare." In the

above story, a low caste man's rage at oppression finds revenge in a second birth,

where he becomes a Brahman.

In

the story of the Transposed Heads (e.g., Yellamma in North Karnataka), both halves

of the above cycle can be seen together. Here a sage suspects his Brahman wife

of infidelity, if only in thought, and asks his son to behead her. In her distress

this woman embraces an untouchable female, and both their heads are cut off simultaneously

by the angry boy. Then the sage relents, grants both women new life, and asks

his son to put their heads back on their bodies. In the confusion, however, these

two heads become transposed. Now two goddesses are created, one with a Brahman

boy and untouchable head, the other with an untouchable body and Brahman head.

In this folktale, then, Brahman and untouchable bodies become merged, each trunk

led by a head of the opposite social category.

King >Low Caste, and Low Caste >King

The

story of Hariscandra who becomes an attendant at the cremation ground as a can?d?ala,

or of Draupadi becoming a chambermaid in the mahabharata are good examples of

kings who become transformed into low status persons much as Brahmans sometimes

are. Similarly, low caste persons sometimes become kings in Indic folktales. In

a story form Bangaladesh a barber boy eats the magic heart of a bull (variant

of the magic bird heart motif), and is reborn as a Brahman. He subsequently arrives

in a kingdom where a king has just died. According to custom in that area, an

elephant is sent out with a garland to seek a new ruler. The elephant garlands

the Brahman youth and he becomes the next monarch. Here the sequence Low Casteè

(Brahman) èKing is seen.

Brahman

>King, and King >Brahman

In

a tale from Kashmir, a cruel king falls ill and dies. But the soul of a sage then

enters his body and he is soon revived. Sri Bhat, a wise minister, sees that this

transformation involved the change from a cruel king into a good one. he therefore

burns the body of the sage so as to prevent the sage's soul from returning to

its original container. By this strategy he forces it to stay on in the (now good)

king's body. In this story then a Brahman (or sage) becomes a king. Several epic

characters like Dron?a, born as Brahmans, similarly take on the marital qualities

and duties of Ks?atriyas. In Vis?vamitra, we have the opposite transformation.

Here a Ks?atriya becomes a Brahman sage (brahmars?i). Now it is an uphill struggle,

both in terms of effort and in terms of social categories.

In

all of these examples there is an implicit cycle characterized by movement along

the path high à low à high, never lowà high à low.

A half cycle, either high à low, or low à high, could perhaps be

called a module or part of this larger sequence which returns to its initial,

high, starting point as a fitting conclusion. The strong oppositions are thus

Brahman low caste, and Brahman/ Ks?atriya; they account for most of the transformations,

and the most dramatic ones.

The

sage / Brahman opposition is weak by comparison and so is sage / low caste. A

sage resembles a Brahman, both in common folk stereotypes and according to philosophical

theory. Yet the transformation from sage to a low caste man does not discomfort

a sage as it does a Brahman. Instead, as in the case of both Siva and Gandi, the

sage may seek a service or outcaste status gladly. Hence the "weak"

quality of this final type. It holds within it little tension or surprise.

So the basic

structure of transformations in Indic folktales resembles the outline for Hindu

social organization more generally:

The

sage could be said to reside outside the system, which could equally be described

as its still center, especially where the traditional metaphor of the wheel of

life is brought into play.

Finally,

one can find stories where all these major possibilities operate in sequential

fashion, so as to produce the extended cycle of Brahman è low caste è

Brahman (memory) è Ks?atriya è low caste è Brahman. The following

folktale from Kashmir illustrates this well. A Brahman's soul once left his while

he was at the river saying his morning prayers. This soul then entered the body

of an infant cobbler. The cobbler grew up among cobblers, married, and had children.

But one day he suddenly became aware of his previous high caste origins and therefore

abandoned his cobbler life and family. He then wandered off and arrived in another

country. There he was chosen king by an elephant who chose to garland him in the

traditional fashion. Afterwards the king ruled this country for some years. However,

his cobbler wife came to recognize him and eventually rejoined him. The king's

subjects were horrified when they discovered his low birth. They then began to

leave his court and country in disgust. The king responded by immolating himself

in a fire. His soul next reentered the Brahman body that was still worshipping

at the river bank. This Brahman then returned home, as if he had woken up form

a strange dream. His wife asked him, "Why did you came back from the river

so soon?" he was baffled by his wife's question and wondered whether his

life as cobbler and king has been a dream. Just as he became lost in wonder, a

beggar arrived at his door and told him he had just come from the kingdom where

the king was disgraced when identified as a cobbler.

The

above story is fascinating for its interweaving of hallucination and reality,

and because of its parallels with classical traditions. No sage is mentioned,

but the play on memory and mirage make the sense of illusion and of meditation

central to all six transformation described.

Conclusion

Our

workshop discussions attempted to move away from earlier folktale classification

schemes that rest on concepts of type, motif, function and genre. Instead we tried

to move towards patterns that might be found to be special to Indian materials.

We also ignored the conventional distinctions between legend, myth and tale. And

we did not concern ourselves with a separation of classical and local materials.

While oppositions and transformations exist in all folk traditions, we argued

that the following three might be particularly important keys to the study of

Indic examples:

high

/ low

power / purity

inside / outside

These

basic themes and transformations transcend genres and distinctions like myths

/ folklore and can best be identified by comparative or complementary studies.

This workshop provided a starting point in the search for newer, more culture-specific

models.

| Brenda

E.F. Beck

University of British Columbia | A.K.

Ramanujan

University of Chicago |

1. This paper was generated from the discussions at

the Workshop on Myth and Folktale held during the Indo-American Seminar on Indian

Folklore at the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore. The participants

at the workshop were: Brenda E.F. Beck and A.K. Ramanujan (coordinators and editors),

Jan Brouwer, Jawaharlal Handoo, Lalita Handoo, A. Hiriyanna, Mazharul Islam, Raghavan

Payyanad, Ramachandra Gowda, and David Shulman.