THE RELEVANCE OF SOUTH ASIAN FOLKLORE

A.K. Ramanujan

University of Chicago

PREAMBLE

Folklore, both verbal and non-verbal, is an excellent quarry for "indigenous"

systems![]() 1.

In non-specialized genres like proverb, joke, game, riddle, omen, or folktale,

as well as in the more professional oral epic or folk-drama, such systems are

embedded, enacted, transmitted from childhood -- especially in a still largely

non-literate culture like South Asia. Yet, till recently, neither humanists nor

social scientists have taken such materials seriously. This is partly because

folklore requires an intimate knowledge of local dialects on the part of the foreign

scholar, or a certain open-minded respect for the deeply familiar on the part

of the native scholar -- both of which have been rare.

1.

In non-specialized genres like proverb, joke, game, riddle, omen, or folktale,

as well as in the more professional oral epic or folk-drama, such systems are

embedded, enacted, transmitted from childhood -- especially in a still largely

non-literate culture like South Asia. Yet, till recently, neither humanists nor

social scientists have taken such materials seriously. This is partly because

folklore requires an intimate knowledge of local dialects on the part of the foreign

scholar, or a certain open-minded respect for the deeply familiar on the part

of the native scholar -- both of which have been rare.

But in the last decade, a new wave of interest has swept the field both in India and in the U.S. The language programs of the 60's in this country have produced a significant number of field-workers capable of working directly in the languages of the area -- notably in literature, history, and anthropology. In India, the literature departments have begun to include linguistics and folklore, and become interested in notions of "region", "tradition", and "folk". Marga and desi, an old Indian pair -- loosely translated as "classical" and "folk", technical terms in native discussions of literature, music, drama and dance - have been linked to, or reincarnated as, "Great and Little Traditions". These interests have naturally led to the collection and analysis of regional folk-materials. For instance, in a language like Kannada, over 200 books were published in the field of folklore in the last two decades (Nayak 1973); all the three major universities in the Kannada area have opened special departments and publication series for folklore. The data is piling up, and there is a great deal more to be collected.

American (and some British and French) scholars

too are gathering this new/old data: to mention only a few in North America, Brenda

Beck (Tamil), Gene Roghair (Telugu), George Hart (Tamil), Peter Claus (Tulu),

Susan Wadley (Hindi). Ved Vatuk (Hindi, Punjabi), Kali Charan Bahl (Punjabi, Rajasthani),

Karine Schomer (Hindi), A.K. Ramanujan (Kannada, Tamil), V. Narayana Rao (Telugu).

These and other scholars have a great deal of material yet to be published, yet

to be analyzed. This is the time to ask new questions of the data we have here,

and, with our Indian colleagues, to make connections with wider points of view.

I the study of South Asian conceptual/perceptual systems also, we think, this

is the next step to take: from written, classical Sanskritic text, ritual, and

commentary to the oral, ever-available texts of folklore that come with living

contexts of use, exegesis and performance.

II. WHY FOLKLORE?

About two decades ago, the teaching and research of Indian civilization in the

U.S. changed, because regional languages like Tamil and Bengali were added to

and required by our studies. (The causes for this shift were not entirely academic,

and merit a separate inquiry). No longer were Sanskrit and classical India deemed

enough to represent the "many Indias". Ideas like the "Great and

Little Traditions" became important in anthropology, and the controversy

over them stimulated the search for finer detail and more adequate conceptions.

The next task to be undertaken is at least two-fold: (a) to deepen our work in

the regional language, to go beyond literacy and text to the pervasive, non-literature,

verbal and non-verbal![]() 2,

expressive systems: tale, riddle, dance, game, curse, gesture, design, folk-theatre,

folk-healing and folk science; and (b) to integrate them, may be by contrast,

may be by tracing possible underlying or over-arching connections, with our knowledge

of classical systems carried both by Sanskrit and by the standard regional languages.

There is, of course, the challenge of relating such materials to the human sciences

-- which is leading us to think of new fields and topics like medical anthropology,

or the relevance of Hindu mythology of folklore to psychoanalysis, and vice versa.

2,

expressive systems: tale, riddle, dance, game, curse, gesture, design, folk-theatre,

folk-healing and folk science; and (b) to integrate them, may be by contrast,

may be by tracing possible underlying or over-arching connections, with our knowledge

of classical systems carried both by Sanskrit and by the standard regional languages.

There is, of course, the challenge of relating such materials to the human sciences

-- which is leading us to think of new fields and topics like medical anthropology,

or the relevance of Hindu mythology of folklore to psychoanalysis, and vice versa.

This may force us to re-examine the notion of the Great and Little Traditions carried by Sanskrit as a "father-tongue" and by the standard regional "mother-tongues". Further complexities of difference and interaction and "affective presence" will be suggested when we enter the dialectal, so-called sub-standard, sub-literary world of folk materials, available everywhere in city as in country, among the literate and the non-literature. Would we find there just broken-down classical mythologies, garbled versions of what we already know, or inversions and transformations, or would we find alternatives, always quick and active, but never fully acknowledged by the written texts? I suggest, in this paper, that we might find co-existent "context-sensitive" systems in South Asia, held and used deftly and pervasively to perceive and solve the culture's special dilemmas.

Different genres (as defined by the culture) like myth and folktale, epic, legend and anecdote, proverbial or classical wisdom (whether in a Sanskrit subhaÀita or a Tamil kural), dance and systems of everyday gesture, may all affect each other, and yet have different contextual functions. They may contradict each other (as different proverbs do, within a language) when treated as a single facetless systems, but they would be seen as viable, flexible "strategies" when treated in context. In cultures and in languages, there are rules of structure and there are rules of use: novel is only one-half of creativity; appropriateness is the other half. This context-sensitivity is, I think, systematic; not just piecemeal and opportunistic, as a whole Western sociological tradition suggests, beginning with Max Weber, ("rationalized Vs. traditional"), or made famous here recently by Levi-Strauss' bricolage, the ghost of which lingers in Sherry Daniels' useful "toolbox" notion (1977; see also Ramanujan 1980 on context-sensitive systems).

Folklore (where ethos, aesthetics, and worldview meet) is an excellent place to examine such notions. For instance, classical texts like the Ramaya¸a and Cilappatikaram present no unchaste women; or, where they are presented, they are chastened by unchastity (ahalya, etc.). But folklore is full of ingenious, promiscuous betrayers of the ideal. I legend, women saints break every rule in Manu's code-book, disobey husbands, take on divine liaisons, walk the streets naked. Such contrasts between 'classical' and 'folk' materials may imply more than one system; they are crucial to our very ideas of conceptual/perceptual systems in a culture.

One may summarize some other features of folklore, that make it especially useful in comparative and other studies:

(a) Folklore displays similar surface structures, with different functions, uses, meanings: a proverb like "It's dark under the lamp" occurs in hundreds of versions, within and outside India, and it means different things in different cultures, even in different contexts within a culture. Bibliographic tools like indexes of types and motifs, are available on a world-wide scale, and also for South Asia. Based on these, sensitive cross-cultural, cross-regional, cross-media comparisons like the ones we are suggesting here, need to be done. I turn, such comparisons may question and revolutionize the indexes, types etc. in the study of folklore.

(b) Text and context are available at eh same time. The new pragmatics and semiotics should find South Asian Folklore particularly exciting.

(c) Intertextuality - a synchronic body of 'texts' can be reliably collected for person, class, place, time or area.

(d) Functional differentiation can be studied for different genres, types etc., and according to sex, age, occasion and so forth.

(e) A great range of connections and interplay can be explored not only among folk-genres, but between folklore and other parts of the culture (medicine, economy, conceptual schemes, classical texts etc.)

(f) Individual oral exegeses, by the composers, tellers, as well as listeners can be collected and analyzed.

Contrasts with other kinds of material (like written literature, historical records) are obvious and need not be labored here.

We have known for some time that we need to test various "Western/universalistic" schemes against new materials. South Asian folklore is a good place for such testing. For instance, Freddian and Piagetian schemes of emotional or cognitive or moral development could be tested against Indian folktales, child-rearing practices, and the role of folklore in indigenous methods of education. What kinds of tales are told or not told to children of certain ages? How do Indian Oedipus tales look? One may examine many Indian Lear-tales that have sons (instead of daughters) as the Cordelia-figures; and in the Kannada "Narcissus-tale" the hero is androgynous, marries his own left half (like Adam?), and is destroyed by her. How do these tales square with (a) other Indian patterns and values and (b) Western schemes (e.g., psycho-analysis) of understanding familial relations? Does Hsu's notion of the importance of different dyads (husband/wife, mother-son, etc.) for different cultures fit Indian culture? Do classical and folk materials agree in this respect? A triangulation, a comparison between South Asian and Western materials as well as a comparison between folk and classical materials, would be instructive.

New research could explore many other relationships: folklore and history; the effect of theoral/written modes on cognitive styles, and on each other; the adequacy of our present notions of oral and written media (e.g. Goody 1977): folklore as a source of central metaphors; metafolklore (e.g., tales about tales); and conceptions of narrative, poetry and aesthetics.

In this working paper, I shall examine five of these questions in detail. My examples will be drawn mostly from me and my colleagues' fieldwork in the Kannada area. I hope what is presented here will serve to point to similar, as well as new, questions, doubts, terms and materials elsewhere. I shall close this section with a couple of my biases:

(1) We said earlier that aesthetics, ethos and world view meet in expressions like myth and folklore. In our discussions of myth and folklore, very little is usually said about the first term of the three. Without aesthetic impact, expressive culture would have neither its immediacy nor prevailing power. I studying Indian concepts like Karma, we have necessarily studied explicit categories of thought - but not ways of feeling. We have studied world-view without ethos, ethos without aesthetics, strands without texture. Folklore items have an aesthetic presence that must be experienced, and thereby explored, for themselves. Every folk-text, even a verbal one like a proverb, is a performance. One should not be too quick to "rescue the said from the saying", but dwell on the saying in its oneness with the said, before we extract the latter. This is, of course, best done in the original language and in performance. Unfortunately, this is only a paper, and in English. Here we can only point to the original - knowing full well that "the pointing finger is not the moon".

(2) Things like folktales are not merely illustrative, but creative of values; not a repository of "indigenous systems", but cultural forms in their own right, which participate in other cultural forms. Having a density of their own, they refract as well as reflect. It would be useful to begin by assuming the independence of folklore (especially in its oral forms) as evidence for cultural inquiry, and not subsume it as an instance or component of other or larger or better known systems till we find reason to do so. While it is reasonable to believe that oral traditions share certain basic ways of thinking, certain metaphors, motifs, favorite logical devices of the "entire" culture -- I would like to hold such beliefs lightly, and not as prove or a priori truths. For there is plenty of reason to suspect that oral traditions may contain themes, emphases, stances, and categories not easily found elsewhere in this culture.

(3) We need to favor a soft-hearted structuralism, with thoughts like Wittgenstein's "form is the possibility of structure" - attentive to individual forms and texts, yet seeking structure, continuity, universals, but seeking them as St. Augustine sought chastity: "Make me chaste, Lord, but not yet".

I. METAFOLKLORE

There are metatheorems in mathematics and logic, ethics

has its Linguistic oversoul, everywhere lingos to converse about lingos are being

contrived, and the case is no different in the novel … in which the forms

of fiction serve as the material upon which frontier forms can be imposed. (Gass

1970 : 24-25)![]() Anyone

interested in native categories must look for the native categories that comment

on native categories - the native metalanguage. Users of folklore, like the users

of other forms of communication, have a number of ways of talking about folklore.

Following logicians and linguists (Jackbson 1960) folklorists have begun to recognize

a metalanguage, a metafolklore which is internal to the folklore they are studying

(Dundes 1966, Babcock 1977). There are metafeatures within a genre like narrative,

and there are metaforms that take narrative, and there are metaforms that take

narrative itself as their subject. There are proverbs about proverbs, stories

about stories. There are also elements in the context or the telling of a tale,

proverb, or riddle that remind us that we are in the presence of a tale, proverb

or riddle, -- elements that frame them and implicity name them as certain generic

forms.

Anyone

interested in native categories must look for the native categories that comment

on native categories - the native metalanguage. Users of folklore, like the users

of other forms of communication, have a number of ways of talking about folklore.

Following logicians and linguists (Jackbson 1960) folklorists have begun to recognize

a metalanguage, a metafolklore which is internal to the folklore they are studying

(Dundes 1966, Babcock 1977). There are metafeatures within a genre like narrative,

and there are metaforms that take narrative, and there are metaforms that take

narrative itself as their subject. There are proverbs about proverbs, stories

about stories. There are also elements in the context or the telling of a tale,

proverb, or riddle that remind us that we are in the presence of a tale, proverb

or riddle, -- elements that frame them and implicity name them as certain generic

forms.

Confining ourselves to narrative forms, there are at least five kinds of metafolklore that one could attend to, that tell us how to 'read' such folklore.

Metafeatures:

a) Elements in the text: e.g. opening

and closing formulae; repetitions; framing devices; forms like prose, verse, song;

identifying devices like names of persons; other textural elements like shifts

in tone and register.

b) Elements in performance: e.g. gestures, asides to

the audience, by which tellers separate themselves.

c) Elements in context:

e.g. festival, puja (worship) performer signified by caste-marks on his forehead,

costume and language.

d) Distinctions and names of genres: e.g. myth/folktale,

marriage riddles, mother-in-law tales.

Metaforms:

e) Tales

about tales, about their forms and functions.

f) Oral exegesis and evaluation

by performer and audience: e.g. favorite tale, notions about what makes one tale

better than another.

For Indian materials, we have very little information about this kind of self-orienting metalanguage. I shall illustrate here just two kinds of data: labels and classes of Kannada songs, and tales about tales.

There is no traditional Kannada term for "folklore", just as there are no terms for what in English would be called 'nature', 'myth', 'religion'. Recently a Sanskrit term has been adopted: janapada. Nor are there clear terms for distinctions between 'oral' and 'written' literature. There is, however, a distinction between marga and desi. Marga means 'the (royal?) road; desi, 'of the country, local'. 'Folklore' would fall under desi, but not all desi song or literature would be folklore.

And there are genre-labels for what in English we would call a proverb (gade), riddle (ogau), folktale (ajji kate 'grandmother's tale'), tale in verse (lava¸i) -- but none for genres like jokes or marchen for instance, though one may collect items that fit a broad description of these types. Unlike English, Kannada has a number of song-types which are restricted to women (he´gasara ha·u 'women's songs') -- songs sung while milling and pounding grain, putting the child to sleep, nuptial songs, marriage songs, satiric songs against new in-laws, as well as songs sung during women's festival and ritual (e.g. for the goddess Gauri) -- with special names for each song-type. So too there are men's songs sung while threshing, bringing grain home, ploughing, as well as male festival songs (e.g. Holi). There are, of course, songs common to both sexes. Furthermore, there are verse narratives sung by male professionals, genres named often after the instruments (e.g. cau·ike, a one-strong instrument) or the caste-name of the singer (e.g. Gondaliga).

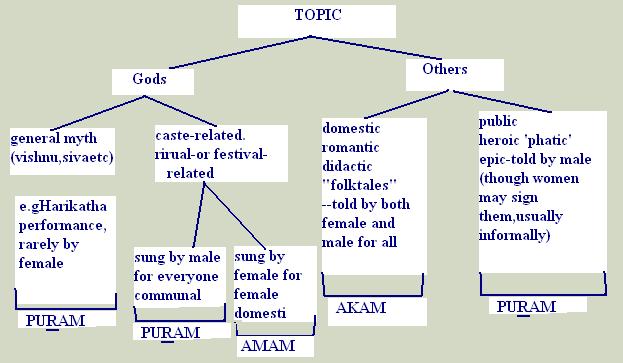

Such genres are cultural categories. The same tale, (e.g. The Tar-baby Type) can be 'ethnical fable' (nitikate) in The Panchatantra, a 'birth-tale' (jataka) about the Buddha, a trickster myth in Africa, and when exported in Uncle Remu's Brer Rabbit Tales a 'children's story for bedtime, or retold in comic books and Disney movies. The division between myth and folktale too is a generic one, and the line is drawn differently by different cultures. To my present knowledge, in Kannada and Tamil, they seem to correspond to a pair of complex categories best named by the classical Tamil terms akam ('interior') and puram ('exterior') - which subsumes distinctions seen in these songs of male/female and lay/profession. Folktales (mostly told by women to children) have to do with akam themes - family, household, sibling rivalry, growing up, love separation and reunion myths deal in puram themes -- society, war cosmos. There are no mother-in-law tales in Hindu mythology; and there are no epic wars the Churning of the Ocean in Indian folktales.

I have written elsewhere about akam and puram distinctions in classical Tamil poetry (Ramanujan, 1967, 1971; and 1980; see also Egnor, 1978 for its relation to conceptions of male and female in Tamil culture). More recently (Ramanujan, 1979) I have spoken of its relevance to a typology of Kannada narrators. This distinction might prove useful to other Indian areas, and may even be suggestive of new distinctions in other areas of the world.

The akam/puram, interior/exterior, distinction is not to be mistaken for the English private/public distinction Akam may include the notion of privacy, domestic but not individual privacy -- of which there is little of it in Indian folklore or literature. It is better translated here by terms like 'familial, domestic'. In topic, theme, setting, clientele and kinds of tellers, Kannada folk-genres seems to be distinguished by akam/puram divisions. Here's an example.

The song-types and enumerated earlier could be similarly distinguished. They give us a clue to the underlying central cultural distinction that we have tentatively called akam/puram after the classical Tamils. One of the important characteristics of akam or interior poetry is that there are no names of places or persons in it; in puram, names are obligatory. One finds a similar difference between Kannada folktales (akam) and (puram). Furthermore, as the same tale moves from the domestic akam teller and sphere to a public context when told by professional bard, the style and motifs (but not always the central structures) change. For instance, the tale of the Three Golden Sons (Type 707) is told by both women at home to children and by itinerant bards. I shall compare the opening sections of a tale from my collection and from the bardic rendition in Paramasivaiah (1971 : 27-45).

A king has five queens and all of them are childless.

The king, one day, finds

and marries a young woman

who bears him a child.

In the domestic version, there is no preamble:

There was a king. The king had four

wives. He was

fearfully rich. He used to eat from a golden plate, drink

from a silver pitcher. Even though he was so rich, he

didn't have any children.

Even in Paramasivaiah's summary, the opening section of the 'public' bardic version runs to several pages. The main features are the following:

Prayer to Siva.

Apologies to audience for possible errors.

Description of the city.

Opening

incident: a mendicant refuses to take alms from the

five queens, because they

are barren and insuspicious.

So the king does on a quest.

He finds Kadasiddamma,

his future queen in a temple -

her story is told in detail.

Throughout the recitation the main teller is followed by an assistant, an 'answer', who holds a dialogue with him, asks him questions, and sings with him when he sings. The answer behaves as a representative of the audience, dwelling on the right emotions, expressing their suspense, joy, horror, etc. All the characters have names, even the midwife - all except the five wicked queens, characterized by an effectively amorphous anonymity in the context of all the names in the tale. Thus akam and puram not only characterize topics, and tale/myth distinctions, but certain moods and techniques as well. For further details see Ramanujan, 1979.

I would like to close this section with three tales about tales -- each illustrating a different aspect of folklore. The first one comes from untouchables who live outside the village; they believe they have a greater treasure of tales than anyone in town. When my friend (Sesha Sastri, 1975) asked them why they would have more tales, they told him the following:

People in the world were bored. So they went to heaven (sarga) and brought back a cartload of stories. As they approached the village the cart broke down and spilled most of the stories near the untouchable colony. The people of the village did get the cart moving, and did get some stories into town but they were very few.

The story speaks of certain compensation that the untouchables find or fancy for themselves for being untouchables and being outside the town. In this context, it may be worth remembering the traditional association of untouchable castes with music, drumming, magic, song and story -- the name paraiyan in Tamil is derived from parai 'drum'. Many of the classical Tamil bardic names are the names of untouchable communities -- e.g. pan?an (Hart 1975 : 125).

There is the notion that tales get fewer as you get into town, and that tales physically came from heaven, no less. It would be interesting, in the light of this story, to collect and compare the tales of this community with those within the village.

The second story (from Dharwar, Li´gan?n?a 1972 : 50-51) speaks of the need for telling stories.

A housewife knew a story. She also knew a song, but she kept them to herself, never told anyone the story nor sang the song.

Imprisoned within her, the story and the song wanted release, wanted to run away. One day, somehow the story escaped, fell out of her, took the shape of two shoes and sat outside the house. The son took the shape of something like a coat and hung on a peg.

The woman's husband came home, looked at the coat and shoes, and asked her - "who is visiting?"

"No one", she said.

"But whose coat and boots are these?"

"I don't know, she replied.

He wasn't satisfied with her answer. He was suspicious. Their conversation was unpleasant. The unpleasantness led to a quarrel. The husband flew into a rage, picked up his blanket and went to the Monkey God's temple to sleep.

The woman didn't understand what was happening. She lay down alone that night. She couldn't sleep for a long time. She asked the same question over and over: Whose coat and boots are those? Baffled and unhappy, she put out the lamp and went to sleep.

All the flames of the town, once they were put out, used to come to the Monkey God's temple and spend the night there. All the lamps of all the houses were represented there -- all except one, which came late. The others asked it, "why are you so late tonight?"

"At our house, the couple quarreled late into the night", said the flame.

"Why did they quarrel?"

"When the husband wasn't home, a pair of shoes came into the verandah, and a coat somehow got on to a peg. The husband asked her whose they were. The wife said she didn't know. So they quarreled.

"Where did the coat and the boots come from?"

"The lady of our house knows a story and a song. She never tells the story, and has never sung the song to anyone. The story and the song got suffocated inside; so they got out and have turned into a coat and a pair of boots. The woman doesn't even know.

The husband, lying under his blanket in the temple, heard the lamp's explanation. His suspicions were cleared. He slept peacefully till dawn and went home. He talked to his wife about her story and her song. He discovered she had forgotten both of them.

Here again the physical nature of stories, the necessity to tell them to keep them alive, as well as the atmosphere of suspicion and rancor bred by a story festering untold - are worth noting. It is also worth noting that even the flames of a lamp are not truly put out -- they just move to the temple for a gossip session. Neither story nor flame is ever destroyed -- they only change their place or shape, with interesting consequences. The gossiping lamp-flame motif is a common one in Kannada tales -- one of the devices by which secret information is revealed (like bird or animal talk overheard by the hero who understands animal languages, Motif B210). The various ways in which information is transmitted in these tales are worth studying (Propp 1970).

The third story (from Tamil) is related to the second one. The psychology lesson contained in it needs no comment.

A poor widow was living with her two sons and two daughters-in-law. All four of them ill-treated her every day. She had no one to who she could turn and tell her woes. As she kept her tale of woe to herself, she grew fatter and fatter. Her sons and daughters-in-law mocked at her figure growing bigger by the day. One day, she wandered away from home in sheer misery and found herself in a deserted house in the outskirts of the town. She couldn't bear her miseries any longer. So she told all her tales of grievance against her first son to the wall in front of her. As she finished, the wall collapsed and crashed to the ground in a heap. Her body grew lighter as well. Then she turned to the next wall and told it all her grievances against her first son's wife. And down came that wall, and she grew lighter still. She brought down the next wall with her tales against her second son, and the remaining fourth wall, to, with all her complaints against her second daughter-in-law. Standing in the ruins, she felt light in body; she looked at herself and found she had actually lost all the weight she had gained in her wretchedness. Then she went home.

II. KARMA AND ITS ALTERNATIVES

One of the straightforward sources of 'native categories' is an inventory of the explicitly named ones like karma, dharma, rasa (in Sanskrit), akam and puram (in Tamil). Any study of such categories requires not only a collection of loci classici but further analysis in terms of components (e.g. causality for karma, contexts (e.g. misfortune)), signifiers (in gesture, story, philosophic terminology, horoscope, etc.), and related terms (like dharma, or puruÀaprayatna, "man's efforts" etc.). Much attention has recently been paid to the technical category of karma (O'Flaherty, ed. 1980). The term is used and discussed widely, and variously, in epic, didactic, and philosophic texts in Sanskrit as well as in Tamil and other regional languages. It is often chosen as a, if not the, representative, pan-Hind, even pan-Indian, concept. Let's see how it appears in the light of Kannada folktales.

"Karma" can be usefully analyzed into at least three independently variable components:

a) Causality : Any human action is non-random; it is motivated and

explained by previous actions of the actors themselves.

b) Ethics : Acts are divided into 'good, virtuous' and 'bad, sinful'; and former accrue pun?ya 'merit', the latter papa 'sin' (?), demerit.

c) Re-birth or re-death,

(punarjanma or punarmr?tyu):

Souls transmigrate, have many lives in which

to clear their ethical accounts. Past lives contain motives and explanations for

the present; and the present initiates the future. The chain or wheel of lives

is called samsara, release from it is mokÀa (salvation, liberation), nirvan?a

('blowing out'), kaivalya ('isolation') in different systems.

Each of these three elements may, and often do, appear in India and elsewhere in different combinations. For instance, Freudian psychoanalysis depends on (a) but not on (b) and (c); utilitarian ethics on (b) and on a version of (a) in its 'calculus of consequences'. Biblical sayings like "Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap", depend on (a) and (b), without (c). certain theories of rebirth may or may not involve(a) and(b): in ideas such as the phoenix rising from its own ashes, or Sa´kara's conception that 'the Lord is the only transmigrant' (Zeahner 1969).

It seems to me that the combination of all these three elements category, as defined above, in Kannada folktales. Here is a folktale with variants recorded for six different districts, told by different castes:

The Lampstand Woman (dipada malli)

A king had a only daughter. He had brought her up lovingly; he had spread three great loades (kadunga) of flowers for her to lie on and covered her in three more, as they say. He was looking for a proper bridegroom for her to lie on and covered her in three more, as they say. He was looking for a proper bridegroom for her. In another city, another king had a son and a daughter. And he was looking for a proper bride for his son.

A groom for the princess: a bride for the prince. The search was on. Both the kings' parties set out, pictures I hand. On the way, they came to a river, flowing rather full and fast, and it was evening already. 'Let the river subside a bit, we can go at sunrise, 'they said, and pitched tents on either side of the river for the night.

Morning came. When they came to the river to wash their faces, both sides mat. This one said, "We need a bridegroom"; that one said, "We need a bride". They looked the pictures over, and liked them. The bride's party said, "We've always spread for our girl three great big measures of flowers and covered her in three more. That's how tenderly we've brought up our girl. If anybody promises us that they will look after her better than that, we'll give them the girl". To that, the groom's party said, "If you spread three great measures of flowers, we'll spread six". There was an agreement right there.

The rain gave them a sprinkle. The wind god dusted and swept the floors. They put up canopies big as the sky, made sacred designs on the wedding floor as wide as the earth, and they celebrated the wedding. It was rich, it was splendid. And the princess came to her husband's palace.

The couple were happy. They spent their time happily -- between a spread of six great measures of flowers, and a cover of six more.

Just when everything was fine, Mother Fate appeared in the princess's dream, and said "Hey, you, you've all this wealth. No one has as much. Who's going to eat the three great heaps of bran and husk?" so saying, she took away all the jasmine, and spread green thorn instead. The girl who used to sleep on jasmine, now had to sleep on thorn. Everyday Mother Fate would come, change the flowers, make her bed a bed of thorn, and then she would disappear. No one could see this, except the princess. The princess suffered daily. She suffered and suffered, got thinner and thinner till she was as thin as a finger. She didn't tell anyone about Mother Fate coming and going, nor about the bed of thorn she spread. "My fate written on my brow is like this. Look what's happening to me", she said to herself, and pined within herself.

The husband wondered why his wife was getting thinner by the day. He asked: "you eat very well. We look after you here better than they did at your mother's house. Yet you're pining away, you're getting thin as a reed. What's the matter?" The father-in-law, the mother-in-law, and the servant maids, all asked her the same question. When Mother Fate herself is giving her troubles that should never be given her troubles that should never be given to anyone, what's the use of telling it to ordinary humans? - it's better to die, she thought, and asked for a crater of fire. She insisted on it.

She was stubborn. What could they do? They finally did what she asked. They robed her in a new sari. They put turmeric and vermilion on her face. They decked her hair in jasmine. They piled up sandalwood logs for the pyre, sat her down in the middle of it and set fire to it. Then, invisibly, a most astonishing thing happened. A great wind came, picked her out of the burning log-fire, raised her unseen by others' eyes into the sky, and left her in a forest. "O god, I wanted to die in the crater of fire, and even that wasn't possible", she said, in utter sorrow.

When the wind died down, she looked around. A forest. A cave nearby. "Let a lion or tiger eat me, I can die at least that way", she thought, and entered the cave. But there was no lion or tiger I there. There were three great measures of bran and husk heaped up -- and a pestle, a pot. She wondered if this is what Mother Fate meant when she said in her dream, "Who's going to eat the three heaps of bran and husk?" What could she do? She pounded the bran each day, made it into a kind of flour, and lived on it. Three or four years went that way. Al the stock of bra and husk dwindled and disappeared.

One day she said to herself, "Look here, it's three or four years since I've seen a human face. Let's at least go and look", and came out of the cave, and climbed the hill. Down below, woodcutters were splitting wood. She thought, "If I followed these people, I can get o a town somewhere", and came down. The woodcutters bundled their firewood, and started walking towards a market-town, a town somewhat like Bangalore. As they walked on, she waked behind them, without being seen.

As the men walked, the sun set in the woods. They stayed the night under a tree. She hid herself behind a bush. Then she saw a tiger coming towards her. "At least this tiger will eat me up. Let it!" she said, and lay still. The tiger came near, growling. But when he came very close, he just sniffed at her and passed on. She felt miserable and she moaned aloud, "Even tigers don't want to eat me". The woodcutters heard her words. They got up and look around. They saw a tiger walking away from where she was. They were stunned with terror. When they could find words, they talked to her: "What a fine woman you are! Because of you, the tiger spared us. But why do you cry? What's your trouble?" She begged of them: "I've no troubles. Just get me to somebody's house. I'll work there; it's enough if they give me a mouthful of food, and a twist of cloth. Please do that much, and earn merit for yourself". They said, "All right", and took her with them. Nearby was a town, very much like Bangalore. The woodcutters went to the big house where they regularly delivered firewood, and asked the mistress for help "Please take in this poor woman as a servant here", they said. The mistress said, "All right", and took her in. the woodcutters went their way. She started work in the big house and did whatever they asked her to do.

One day the mistress's son threw a tantrum. The mistress said to her, "Take this child out, show him the palace, do something to quiet him down". So she carried him out, and as she was showing him this and that to distract him, a peacock took the child's necklace and swallowed it. She did all she could to coax the peacock to return the jewelry, but she couldn't. She was in trouble. She came running to the mistress and told her what happened, how a strange peacock took her son's necklace. The mistress didn't believe her. "You thief, you shaven widow, you-re lying -- you've hidden it somewhere. Go, bring it back at once", she screamed, and gave her a beating. "No, no, I swear by god. I didn't take it. It's that bird, that peacock! It swallowed the necklace", she cried. They didn't listen to her. The mistress said, "This one is a deep one, she won't budge for small punishments", and gave her a big punishment. She got the young woman's head shaved clean and naked; asked a servant to place a patty of cow dung on it, put an oil-lamp, on it, and light the lamp.

So the poor woman worked at household chores all day. At night, she had to carry the lamp on her head, and go wherever they asked her to go. Everyone called her Lamp Woman. Lamp Woman. Time passed this way.

One day, the mistress's elder brother came visiting. He was no other than the Lamp Woman's had happened. He came to his younger sister's house, dined there, and sat down to chew betel leaf and betel nut. The mistress sent the Lamp Woman to light the place where he sat enjoying his squid of betel leaf. The Lamp Woman knew at once that this man was her husband. She gulped down her sorrow and stood there, with the lamp on her head. He looked at the Lamp Woman, but he didn't recognize her. He really believed that his wife had perished in the fire. He thought this was some woman getting punished for some wrong she had done. And he talked to her in a commanding voice. "Lamp Woman, tell me a story".

"What story do I know, master? I don't

know any story".

"You must tell me some story. Any kind will do".

"Master, shall I tell you about what's to come or about what's gone before?"

"Tell me about what's gone before".

"A story of terrible hardships".

"Go ahead"

The Lamp Woman told him where she was born, how she got married, how Mother Fate appeared in her dream and tormented her on a bed of thorns, how she thought she could escape it all by dying in a pyre of sandalwood, how the wind miraculously rescued her and carried her to a forest, and how she lived there for years on a meal of bran and husk. Then she told him how she came with the woodcutters to this place and entered service; how, one day, the peacock swallowed the necklace when she was consoling the child, and she was called a thief and shave widow, and how she was condemned now to walk about as a Lamp Woman. All this she told the prince, in sorrow. As he heard the story, he began to see who she was; by the end, he knew he recognized her, this was none other than his long-lost wife, and he took down the lamp from her head. He scolded his young sister and brother-in-law for punishing his wife so cruelly. They fell at his feet, pleaded ignorance, and asked forgiveness. He put his wife on horse and left at once for his own kingdom. Everyone there was very happy to see that the princess hadn't really perished in the fire.

After that, the couple lived happily.

(Li´gayya 1971 : 16-20)

The story of the Lampstand Woman is told in the Kannada, Tamil and Telugu areas. I have an example of each from Tamil and Telugu and six variants from several Kannada districts. Of the several things that can be said about it, what is relevant here is the mainspring of the action. What happens to the heroine has nothing to do with her character. It is made clear she is blameless. There is no villainy, no fault. Mother Fate seems a bit jealous of her good fortune. Her speech in the girl's dream makes that clear: "Hey you, you've all this wealth. No one has so much. Who's going to eat the three great heaps of bran and husk?" a psychologically oriented interpreter might see in the Dream an expression of the heroine's guilt over her prosperity, a need to earn it by suffering and hardship. That is plausible, but the storytellers (when I ask them) tell me, it is all because of 'what's written in the forehead', and the will of Mother Fate (Vidhiyamma). Character is not destiny here, nor does the character have to 'learn through suffering' as in western (Greek or Shakespearian) drama.

Vidhi or Fate is usually imagined as a woman, Vidhiyamma in South Karnataka; Seivitayi in Northern Karnataka and Maharashtra (Karve 1950). She writes on a newborn child's forehead all that is going to happen to him or her. Sometimes the Vidhi-function is performed by Brahma. Several expressions refer to this writing on the forehead: talaividi 'head-fate', talaiye"uttu 'head-writing' in Tamil; ha¸eli barediddu 'what's written on the forehead', ha¸ebaraha 'the writing on the forehead' in Kannada; phalalikhita 'what's written on the forehead', brahmalipi 'Brahma's Script' in Sanskrit, and in the Sanskritized dialects of various Indian languages. Some of the former phrases like "vidhi", "talaividi", "talaiye"uttu" are also used as interjections and exclamations when misfortune strikes.

In the Tamil version, the young woman brags she can manage her life with just one grain of paddy; so she is given one grain of paddy and driven out of the house. She toasts it very carefully on sand heated on a borrowed stove, makes a single huge spectacular piece of 'popcorn', and sells that, buys more grain, makes more popcorn, and so o till she gets rich and marries a merchant. But she is thrown out of her husband's house, because he sees one day a big green kamb½imas fruit under her bed, mistakes it for the shaven head of muslim, and suspects her of adultery. After some adventures, she ends up in a brothel where she's suspected of stealing a necklace, and she is given the job of carrying a lamp on her head. One day her husband visits the brothel, and she recognizes him. That night, the lampstand woman takes down the lamp and tells it her entire story. He overhears her tales, understands it, and takes her home.

In this variant too, there is no cause at all for her misfortunes -- in the first part, it is true she bargs, but makes good her brag. But she falls, at the height of her good fortune. A concept like time's whirligig (kalacakra) or 'fortune's wheel' seems to underline the action.

In another Kannada story, "Shall I come at seventy or at twenty?" (Type 938B), a king, his queen and two children are at the height of their prosperity. On her way to the river, the queen is accosted thrice by a bird which says: "Ask your husband when I should come -- at seventy or at twenty?" The husband decides, whatever it is it's better if it comes at twenty when their bodies are still firm and can endure anything. So he asks her to tell the bird he would prefer it to come when he is twenty. When the bird hears this, it follows the queen to her palace, flies in through the front door and goes out through the back. And their misfortunes begin. Suffering defeat, exile, poverty, the king becomes a poor woodcutter. The queen works as a menial maidservant, is molested, abducted and imprisoned in a ship by a merchant. The king is disgraced and separated from his wife for many years. Finally one of his sons wins a kingdom, they meet up with the merchant's ship and rescue their mother from her abductor, and reunite with their father (Hegde 1976).

In this tale, fate is not mentioned; only a sinister mysterious

bird of ill omen brings misfortune. But it gives the king a choice of time, and

he wisely chooses to suffer hardships in youth rather than in his old age. Here

too, there is no sense of past causes or moral responsibility. Compare this with

the Mahabharata where the characters act and suffer for reasons of past karma;

celestial Urva¿i's curse makes Arjuna serve as a effeminate dancing master

for one year in Viraa's court the exile itself is caused by Yudhisthira's wager

at the dice-game, which in turn is caused by Sakuni's vengefulness, and in some

versions by the acts of his and others' past lives. The Kannada folktales depict

action within the span of a single life, no more![]() 4.

4.

Then, too, a god like Sani (Saturn) or a goddess like LakÀmi, if offended may bring misfortune. Many of the vrata stories and stories about Sani's power are of this type.

This kind of tale, The Offended Deity, recognized as Type 939, a special Indian oicotype, is summarized by Thompson and Roberts (1960 : 119) thus:

I. A king offends a deity. He loses his kingdom and his fortune

and is forced to wander in poverty for a term of years. (a) His wife is stolen

from him. (b) He must labor at menial tasks. (c) Taken in and helped by a friend,

he sees a valuable necklace disappear before his eyes. Knowing he will be suspected

of the left, he is forced to flee. (d) He is bought as a slave and is ordered

to throw corpses into a tank and collect a fee. His wife brings the corpse of

their son.

II. The king is eventually resorted to his former position. (a)

His wife (and child) are resorted to him.

Variants have been recorded in Bengal, upper Indus, Punjab, as well as in South India. The story of Hariscandra (Dimock 1963) who is tested and persecuted by Sage Visvamitra, the calamities that befall Cando in the Bengali Manasa narrative (Dimock and Ramanujan 1964), and the Raja Vikrama stories of South India (made into popular movies in Kannada and Tamil) in which the Raja defies Sani (or Saturn) are excellent full-fledged examples of Type 939.

The Sani story is intimately related to astrological beliefs regarding the planet Saturn, and his seven-and-a-half-year sway over a person's life. As a variant, some tales begin with an astrologer's prophecy of misfortune. The story works out the prophecy, despite the protagonists' struggle to escape it. The Indian Oedipus tale told on p. , begins this way. A girl is born and an astrologer prophecies she will marry her own son and bear him children. The rest of the story tells of the fulfillment of the prediction. The prophecies are seen as indicators of future events and there is no question of inner or karma-like casuality or responsibility.

Thus instead of past karma as an explanation of present action, exemplified both in epic story and philosophic debate, these folktales seem to depend on another set of explanatory notions; a) arbitrary vidhi or fate, who writes on the newborn's forehead, often personified as a goddess or a Brahma; b) an offended deity who wants a defiant person to toe his or her line; c) a prophecy that cannot be evaded. Even curses are quite rare, for they are often earned by the individual's own acts.

The overwhelming impression is of the mysterious power of fixed fate, which can only be obeyed and allowed to run its course. Karma seems to belong to another system altogether -- with its complex interweaving of individual responsibility, previous lives, the inexorable chain of ethical judgement and causation. The characters of these folktales live in a different ethos.

Maloney (1974), corroborating an earlier paper by

Harper (1959), and other even earlier observers (cf Elmore's quotes from Lyall

and the Census of 1911, 126-129), note that notions like Karma and re-incarnation

are unknown in some sections of village society. In his Kanakkuppi½½ai

Valasai, a predominantly Ve½½a½a village, people didn't know

about the Vedas, nor had they heard about Sanskrit. This may be an extreme instance.

And diffusion of Sanskritic ideas and patterns does not depend on knowing Sanskrit

or even about it. We know that proverbs, riddles, tales, not to speak of gestures

and beliefs, travel across languages, classes, cultures -- they are autotelic.

All they require is a small number of bi-cultural bilinguals. They do not even

require large-scale migrations, only contact. Tale-type and proverb-patterns,

like the words Karma and dharma![]() 5,

are 'borrowed', freely, but naturalized with local detail, pronunciation, in new

contests with unforeseen meanings. A glance at Archer Taylor's world-wide parallels

in this English Riddles (1951), or the Aarne Thompson tale-type index is enough

to convince us of that. Emeneau (1970) demonstrates Sanskritic poetic motifs in

tribal Toda songs.

5,

are 'borrowed', freely, but naturalized with local detail, pronunciation, in new

contests with unforeseen meanings. A glance at Archer Taylor's world-wide parallels

in this English Riddles (1951), or the Aarne Thompson tale-type index is enough

to convince us of that. Emeneau (1970) demonstrates Sanskritic poetic motifs in

tribal Toda songs.

On the other hand, what's astonishing is the absence of Karma in these tales -- and the tales are not confined to untouchables who haven't heard about Karma. The tales are widely current, shared by different groups and areas; the ones cited here were told by Havyaka Brahmans (Hegde 1976), as well as by Jainas (Dhavalasri 1968), who are fully exposed to notions of karma. "You! Prarabdha! Prarabdha karma!" meaning "you are my accumulated bad Karma!" is a common abusive formula among Brahman parents. Could it be that the Brahman and Jaina women share a view and culture in common with other castes (who may or may not have Karma in their repertoire)? Cold it be that they live in a 'split-level' world -- one Karmic another not? One is reminded of a South Indian wedding, in which there is a Vedic fire ritual presided over by Vedic priests and conducted in Sanskrit, and other ceremonies surrounding it conducted entirely by women where dialectal riddles are bandied about between groom and bride, satiric songs belted out at the new in-laws, and nuptial songs known only to women: it is like the double plots of Shakespearian (or Sanskrit) plays, with multiple diglossia articulating different worlds of the solemn and the comic, verse and prose, the cosmic and the quotidian.

Most of the women's tales are told to boys as well as girls, though there may be some gender-specific tales (I have no data on this, only a suspicion) -- so the men too live in multiple words. Though there are gross and subtle differences in languages and themes from community (yet to be studied), at least in this matter of Karma and its alternatives, Brahman and non-brahman tales are similar. (My data consists of nearly 1000 tales, collected independently by about 12 collectors at different times, place and in different groups over the last 20 years).

This kind of double or multiple

perspective may be only one witness to a more pervasive pluralism. I have suggested

elsewhere (Ramanujan 1980) that in Indian traditions, whether they be legal, medical,

literary or whatever, we have 'context-sensitive' multiple systems![]() 6.

these variant systems are elicited appropriately in well-defined contexts. For

instance, one law does not universally apply to all men in Manu's code -- but

according to the caste and circumstance of the offender or the victim. William

Blake said, "One law for the lion and the ox is oppression", and the

Hindus would have approved. Explanations are not judged by standards of consistency

but of fir (aucitya). The Buddha once spoke of a man who, as he was drowning in

a sudden flood, found a raft. And he was so grateful to the raft that he carried

it on his back all his life. Methods and explanatory systems are no different.

When V. Daniel (1979) asked his Tamil villagers if the stripes on a temple were

white on red or red on white, he received different answers at different times.

Sheryl Daniel found, in her inquires into legal reasoning, similar shifts of argument.

She has also, independently, documented that Karma and 'head-writing' were used

to explain different things. She calls this 'the toolbox approach of the Tamil

to the issues of Karma, moral responsibility and human destiny'. I have preferred

to use a more systemic, linguistic analogy and called the approach 'context-sensitive',

rather than 'tool-box' (Daniel 1977) or 'opportunistic' (Geertz 1973, after Weber),

or bricolage (Levi-Strauss 1966). However we name it, we are in the presence of

complexes and (sub) systems that are sensitive to context, and they are seen that

way by the 'natives' themselves.

6.

these variant systems are elicited appropriately in well-defined contexts. For

instance, one law does not universally apply to all men in Manu's code -- but

according to the caste and circumstance of the offender or the victim. William

Blake said, "One law for the lion and the ox is oppression", and the

Hindus would have approved. Explanations are not judged by standards of consistency

but of fir (aucitya). The Buddha once spoke of a man who, as he was drowning in

a sudden flood, found a raft. And he was so grateful to the raft that he carried

it on his back all his life. Methods and explanatory systems are no different.

When V. Daniel (1979) asked his Tamil villagers if the stripes on a temple were

white on red or red on white, he received different answers at different times.

Sheryl Daniel found, in her inquires into legal reasoning, similar shifts of argument.

She has also, independently, documented that Karma and 'head-writing' were used

to explain different things. She calls this 'the toolbox approach of the Tamil

to the issues of Karma, moral responsibility and human destiny'. I have preferred

to use a more systemic, linguistic analogy and called the approach 'context-sensitive',

rather than 'tool-box' (Daniel 1977) or 'opportunistic' (Geertz 1973, after Weber),

or bricolage (Levi-Strauss 1966). However we name it, we are in the presence of

complexes and (sub) systems that are sensitive to context, and they are seen that

way by the 'natives' themselves.

We have yet to define thee eliciting contexts precisely. The recent work of Zimmerman on Kerala Ayurvedic medicine, the above mentioned work of V. Daniels (on the place of place), and of S. Daniels on Tamil villagers' explanations, and of Appadurai on the legal/social history of a Madras temple (1981) are helping us move towards a better understanding of South Asian contextualism.

We are adding folklore (here, women's tales) as another such context-sensitive systems, or body of material, coexistent with Sanskritic (or lately, even British/Cosmopolitan) Systems.

These (sub-) systems are not to be seen of as characteristic of different social strata (e.g. caste) but as available to the same individuals within them, in different degrees. Together, the various (sub-) systems may or may not make a single super-system. This question is still open; new formulations like Marriott's (1976), may help us define it, if not answer it.

Language models (as hinted, all along) may be pertinent. So far, they have depended on narrow views of what language is, if we include in our consideration of language, rules of structure as well as of use, a semiotics and an ethnography of speaking, a notion of speech repertoires for a individual or a community, -- we may then have ways of talking usefully in linguistic analogies.

The situation I've described regarding Karma in folklore and other kinds of texts (epics, philosophies, bhakti), may be closer to a coordinate bilingualism rather than to a compound one. In coordinate bi- (or multi-) lingualism, two language systems are held and used without too much blurring of systematic distinctions -- such speakers may speak English with an English accent and French with a French accent for both -- e.g. an Indian's phonology for his English and his Tamil may be the same. Furthermore, different sub-systems like phonology, syntax or paralanguage, may be differentially affected and re-structured. I am suggesting that the old dichotomies of classical/folk, Great/Little, sacred/profane etc., may be such co-existent codes "switched" by rules of context -- like the speech varieties in a speaker's repertoire. I am also suggesting that such a conception of "system" itself is an indigenous one.

Once we recognize such

a concept and such a repertoire (Karma, fate, astrology, offended deities![]() 7),

we may look for a pattern. We have not found it yet. We are not yet there. Folklore

is a reminder that we are not. That is one of its relevances.

7),

we may look for a pattern. We have not found it yet. We are not yet there. Folklore

is a reminder that we are not. That is one of its relevances.

III. PSYCHOANALYSIS AND INDIAN FOLKLORE

In 1971, I reported briefly on what I called the 'Indian Oedipus' (Ramanujan 1971). The four nuclear dyads -- Father/Son, Mother/Son, Father/Daughter, and Mother/Daughter -- were the focus of the paper. I suggested that in Hindu myth, regional folklore, and modern literature, there were many examples which reversed the 'Western' oedipal patterns: son as father's rival and assassin (Oedipus, Hamlet, Karamazov). In the Indian examples, we have Father or Father-figures as the sexual and political rivals of sons. In the Mahabharata, BhiÀma takes an oath of celibacy and lays aside his claim to the throne, sacrifices his sexual and political potency so that his father can marry a young fisherwoman. Similarly Yayati asks for and takes his youngest son's potency to renew himself sexually for a thousand years. Such sacrifices of youth and potency at the altar of age, to rejuvenate the Father, are greatly admired in India. In Indian history, there is a remarkable contrast between Hindu and Muslim dynasties. There are no stories at all of patricide in the Hindu dynasties, whereas patricide and aggression towards the father is rife in Muslim dynasties (ibid). If you include elder brothers and gurus as Father-figures (hence the capitals on Father, Son etc.), the pattern is wide-ranging. My 1971 discussion also included Fathers desiring (and also marrying) Daughters; and Mothers marrying Sons. Many Kannada and Tamil tales have the Daughter fleeing an amorous Father (fathers, elder brothers, kings, gurus), often foiling his attempts. For details, I refer the reader to the 1971 paper, and shall speak here only of some things I have learned since, and of implications for our present inquiry.

Folklore seems to be richer in this kind of material than mythology. Furthermore, the tales are current in the Kannada area (I have a variant or two for almost every district of Mysore, for the Mother-marries-Son tale) -- in a way the corresponding Sanskritic myths are not. The relevant Sanskritic myths widely current are those of BhiÀma giving up his sexual and royal potency for his father, of Yayati taking over his youngest son's sexuality, of VasiÀha the brahman sage resisting and finally subduing the rebellious son-figure, the KÀatriya Vi¿vamitra. I am indebted to Goldman (1978) for his detailed further discussions of these myths, and for some of his insights: the Father-Son pattern should not only include the guru/disciple relation, but the Brahman/KÀatriya relation as well. One of Goldman's best demonstrations concern Vi¿vamitra (KÀatriya, as Son), fighting with VasiÀha (Brahman, as Father) for the possession of the latter's wish-fulfilling cow (Mother-figure; cf. gomata); VasiÀha's defence and weapon is his sagely phallic staff (da¸·a) Goldman agrees that there are no clear and major instances of son rebelling against and over-throwing father, but points out rightly that there are many compelling instances of disciples besting and often killing, Oedipus-fashion, their gurus. The pa¸·avas kill Dro¸a and BhiÀma, one a guru, the other a great-uncle as well as guru. Even here, I would insist that the power of the Indian Father/guru is overwhelming. In both cases, BhiÀma and Dro¸a die because they give up the will to live, and allow their son-figures to kill them. In the VasiÀha- Vi¿vamitra case, VasiÀha is never over-thrown. What is clearly seen is the open conflict between guru and disciple, not the Son's passive sacrifices (as in the cases of BhiÀma and Yayati's son) to a father. Obviously cultural biases allow the possibility of a disciple fighting a guru rather than of a son fighting a father. Further, certainly in the folktales, there is also clear admission of fathers desiring and marrying daughters, mothers (however unwittingly) marrying sons. Similarly, though there are no clear tales of mother-daughter conflict, there are scores of examples of mother-in-law, stepmothers and wicked elder queens who try to oppress, maim and kill daughters-in-law, step-children (usually female), and younger queens. Here the outcome and listener's sympathy is on the side of the victims. There are a small number of stories about cruel daughters-in-law (see p. earlier, for an example) persecuting the parent figure. The Mother-in-law is a special Indian figure.

The direction of aggression and desire in folktales is regularly from the elder towards the younger member of the dyad, unlike the European tales. Let me quote and discuss the Mother-Marries-Son tale in detail:

A girl is born with a curse o her head that she would marry her own son and beget children by him. As soon as she hears of the curse, she willfully vows she'd try and escape it: she secludes herself in a dense forest, eating only fruit, forswearing all male company. But when she attains puberty, as fate would have it, she eats a mango from a tree under which a pass-king has urinated. The mango impregnates her; bewildered, she gives birth to a male child; she wraps him in a piece of her sari and throws him in a nearby stream. The child is picked up by the king of the next kingdom and he grows up to be a handsome young adventurous prince. He comes hunting in the selfsame jungle, and the accused women falls in love with the stranger, telling herself she is not in danger anymore as she has no son alive. She marries him and bears him a child. According to custom, the father's swaddling clothes have been preserved and are now brought out for the newborn son. The woman recognizes at once the piece of sari with which she had swaddled her first son, now her husband, and understands that her fate had really caught up with her. She waits till everyone is asleep, and sings a lullaby to her newborn baby:

Sleep

O son

O grandson

O brother to my

husband

Sleep O sleep

Sleep well

and hangs herself from the rafter wit her sari twisted to a rope.

Variations occur, in the eight Kannada examples I have, at the following points in the sequence. In discussing them, I shall also point to their psychological significance.

Variations occur, in the eight Kannada examples I have, at the following points in the sequence. In discussing them, I shall also point to their psychological significance.

(1)

Instead of a curse an astrologer's prophecy initiates the action; or we have vidhiyamma

(Mother Fate) or Seivitayi![]() 8,

who writes their fates on newborn babies' foreheads. Her daughter discovers her

mother's "profession" one night when she returns from a nocturnal visit

to a newborn baby, accost her, and insists on knowing what she wrote on her own

daughter's forehead. When she hears that Mother Fate had written that she (the

daughter) would marry her own son, she flies into a rage and proceeds to defy

her 'life script'.

8,

who writes their fates on newborn babies' foreheads. Her daughter discovers her

mother's "profession" one night when she returns from a nocturnal visit

to a newborn baby, accost her, and insists on knowing what she wrote on her own

daughter's forehead. When she hears that Mother Fate had written that she (the

daughter) would marry her own son, she flies into a rage and proceeds to defy

her 'life script'.

The notion of a child's 'life-script' written by a mother should be interesting to psychotherapists, especially of the Berne-an persuasion. Resistance to a parent's injunction or suggestion yet fulfilling it willy-nilly as if under hypnosis, follows well-known patterns of compulsive behaviour

There are also tales of 'outwitting Fate', finding creative solution by wisely using the very conditions laid down by Fate -- for instance, it is written that a girl is fated to earn her living each night by selling her sexual favors. She is advised by a clever friend to ask for a bushel of pearls as payment for a night, so that no one but a divine being (Brahma Himself, who 'wrote' her destiny) can be her lover; she is also advised to give it all away the next day by which she ensures both her own pu¸ya (accumulating merit) and the certainty of the nightly visit by her divine lover (Sastri 1968).

One should also examine the many stories of a Father or Guru giving his son three or more precepts which will be useful to him in crisis-situations like his wedding night, or when he is lost in strange places or is chosen to be king, or in the hour of danger. As these Precept-stories (Type 910) have variants in other parts of the world, they should be comparatively studied and the special Indian elements could be isolated. For instance, Type 910H-J Never Travel Without a Companion, Stay Awake, Never Plant a Moon Tree, seem to be special to India. Many of the parental percepts save the hero's life especially on his wedding night. In these stories the bride has poisonous snakes which issue from her nostrils; in one, his companion, a crab, kills the snakes; in another, he remembers and follows his father's precept to stay awake and so is able to kill the snakes and make his bride safe to live with. The Freudian gloss about the 'first night' is obvious.

(2) In five of the

variants the girl gets pregnant not be actual sexual intercourse but by eating

a mango from a tree watered by a king's urine. In three other tales, she gets

pregnant by drinking water from a pool in which a king has rinsed his mouth. Either

way, his body fluids (saliva and urine are two of the polluting body fluids mentioned

by Manu - sweat, blood, semen, tears and mother's milk being the others) are treated

as capable of impregnating the woman. In other tales, "blood, sweat, and

tears" are all seen as capable of making babies. It is, as it were, no body

fluid is non-sexual, at least non-procreative. There is also no distinction made

between reproductive and alimentary channels, noted by Freud as characteristic

of the child's view of reproduction![]() 9.

Folklore, here and everywhere, uses common, uncensored, childlike beliefs. (See

also the American hospital joke about the nurse who swallowed a razor blade, and

three doctors were circumcized as a result).

9.

Folklore, here and everywhere, uses common, uncensored, childlike beliefs. (See

also the American hospital joke about the nurse who swallowed a razor blade, and

three doctors were circumcized as a result).

(3) Not all variants contain the lullaby at the end (p.115) which describes the "unnatural" confusion of kinship relationship. Mother marrying son and begetting another son by him collapses generational differences: by this act, son and grandson become one. It conflates the differences between kin by birth and kin by marriage; son and husband become one, so do mother-in-law and mother; and so on. The most fantastic of these kin-confusions is in Jain tales (my examples here are all literary). In some, a courtesan has twins whom she abandons; they grow up separately, meet and marry, but recognize their kinship by the rings they wear; the son travels far, becomes his mother's lover and begets a son; his spouse and sister, who renounces the world, acquires magical vision, comes to warn her mother and brother, sees their son, and addresses him thus: O child; you are my brother, brother-in-law, grandson, son of my co-wife, nephew, uncle. Your father is my brother, husband, father, grandfather, father-in-law, and son. Your mother is my mother, mother-in-law, co-wife, my brother's wife, grand-mother, and wife". (Jain 1977, Appendix-I, 566; for other examples, see Karve 1950; Ralston 1882). It is clear that in Jain examples, the point of the tale is not Fate; nor Oedipal patterns of Mother/son relations, but the destruction of the kinship diagram. Such a confusion of clear-cut kinship relations (son/husband, mother/mother-in-law etc.) would be-devastating to a child, would make a shambles of his ordered family world. That seems to be part of the terror of the incest taboo, and the poignancy of some of the folktales. (The Jain literary tale de-fuses the charge of the tale by its clever elaboration and by overdoing the list of paradoxical relations). The characteristic response to such a disorienting sin in these tales is suicide (of the mother, the heroine) or a renouncing of the world by everyone concerned. Such a renunciation, a withdrawal of all relations, in Indian terms, is a kind of social suicide -- one becomes a sanyasi by performing a funeral rite on oneself.

(4) The end of the tale

is interestingly different![]() 10

in a small number of my variants (Sivakumar 1975) and in Karve's Marathi tale

(Karve 1950); the latter was told by an illiterate Maratha woman to her daughter.

Instead of the heroine killing herself or renouncing the world, she recognizes

that her fate has been fulfilled, doesn't tell anyone about her incestuous marriage,

lives happily with her husband, "blessed by her aged parents-in-law to whom

she was always kind and dutiful". When Karve asked the illiterate Maratha

woman what she thought of it, she replied, "But what else could she do? You

know, madam, it was written so". Not only that; "At the end of the tale

my little daughter and the narrator were both laughing at the queerness of the

happening" (Karve 1950).

10

in a small number of my variants (Sivakumar 1975) and in Karve's Marathi tale

(Karve 1950); the latter was told by an illiterate Maratha woman to her daughter.

Instead of the heroine killing herself or renouncing the world, she recognizes

that her fate has been fulfilled, doesn't tell anyone about her incestuous marriage,

lives happily with her husband, "blessed by her aged parents-in-law to whom

she was always kind and dutiful". When Karve asked the illiterate Maratha

woman what she thought of it, she replied, "But what else could she do? You

know, madam, it was written so". Not only that; "At the end of the tale

my little daughter and the narrator were both laughing at the queerness of the

happening" (Karve 1950).

One of the notable things about this story is that it is told invariably by women and to girls. The protagonists of the story are women; the men are pawns in the story of women's fate. Karve's Maratha woman heard it from her old sister-in-law when she was about 15, and told it to Karve's daughter. All my Kannada variants were collected from older, motherly women. Obviously, fathers and brothers, the males within one's family, are seen as the first temptations for a woman, and vice versa. To withstand (a) the temptation of incest (within the family), and then (b) the temptation of adultery (ineligible men outside the family) seem to be the two successive tests for women before they can mature into wives and mother (Ramanujan 1982).

One of the objects of this exercise is to isolate, if possible, (a) specific Indian patterns, (b) patterns specific to folklore in India. So two kinds of comparisons are necessary; Indian with non-Indian materials, classical Indian with folklore materials. Such a 'triangulation' would show convergences and differences. I have discussed elsewhere a Cinderella pattern in European, Sanskritic, and Kannada examples (Ramanujan 1982). In my 1971 paper, I compared the Greek Oedipus myth with Kannada tale. The Greek myth is central to that culture; it is the object of much literary elaboration and phychological discussion (which is itself a sign of its importance). In it the killing of the father, Laius, is as important as the marrying of the mother. The story is told entirely from the view point of the male, the son: he is the cursed one, he is the one who tries to escape fate and yet fulfills it, he is the one who discovers the truth about himself. The Kannada tale, told by village women, is not the object of similar literary elaboration. There is no Laius-figure, and therefore no patricide, in any of the tales. The tale, in its episodic sequence, in any of the tales. The tale, in its episodic sequence, is exactly the same as the Greek one, but it is told entirely from the woman's, the mother's point of view.

To structural analysis, therefore, we need to add point of view, before we can interpret a tale. One may ultimately decide that such reversals (male to female, son fated to marry mother instead of mother being fated to marry son etc.) as structurally or psychoanalytically reducible to a single pattern. But the presence of such differences should be interpreted in the light of other parts of the culture. It is true that all humans have bodies, everyone has fathers ad mothers; but human also as invariably, live in cultures which rear them on body-images and parent-images. One cannot assume either invariance or uniqueness; they have to be tactfully, sensitively, demonstrated. Folklore with its universal forms (e.g. tale types , motifs, proverb patterns) and local, functionally significant variants, with its motifs and patterns shared both with classical Indian and with non-Indian texts, is specially important for the demonstration of characteristic 'indigenous systems'.

A few other areas of inquiry may be briefly suggested here. We know that patterns of toilet-training are significant in any psychoanalytic interpretation of culture and personality. We also know that Indian patterns of child-rearing are strikingly different from, say, American ones (Kakar 1978 : 103-104). Folktales told to children of toilet-training age (3-5) like the following are significant:

Sister Crow and Sister Sparrow are friends. Crow has a house of cow dung; sparrow, one of stone. A big rainstorm washes away crow's house. So she comes to Sparrow and knocks on her door. Sparrow makes her wait first because she is feeding her children, later because she is making her husband's and children's bed. Finally she lets her in and offers her several places to sleep. Crow chooses to sleep in the chickpea sacks. All night she munches chickpea and makes a kaum-kaum noise. Whenever Sparrow asks her what the noise is, Crow says, "Nothing really. Remember, you gave me a betel-nut? I'm biting on it". By morning, she has eaten up all the chickpeas in the sack. She cannot control her bowels, so she fills the sack with her shit, before she leaves. Sparrow's children go in the morning to eat some peas, and muck their hands up with Crow's shit.

Sparrow is angry. When Crow comes back that

night to sleep, she puts a hot iron spatula under her and brands her behind. Crow

flees, cyring, Ka! Ka! in pain.

Children laugh a lot at this story - especially at the crow filling the sack with her shit, Sparrow's children getting their hands dirty with it, and at Sparrow's revenge. But it is an ambiguous story. Saparrow, obviously a tidy and successful housewife, is not given to incontinence; her house is firm, her routine well-ordered -- analysts would relate these orderly virtues to anal continence (Jones 1918). Crow is disorderly, incontinent, her house of dung cannot withstand a storm; she can neither control her nightlong eating nor the morning's unloading of her bowels. She is punished by branding on her behind. On the other hand, I have always felt a certain ambivalence in myself, and in the tellers and the children, about Sparrow; she keeps Crow waiting in the rain, is not generous in her hospitality. One feels she deserved, somewhat, Crow's untidy return for her grudging hospitality. Children laugh gleefully at Sparrow's discomfiture, and enjoy Crow's filling the sack with shit.

We need to collect similar stories told to children of different ages, and also children's reactions to them. Riddles in America are favored by children at 5-6 - when they are learning basic logical operations of a la Piaget. While that is true in the Kannada area too, and children used in adult occasions - wedding, festivals and competitive riddle-matches. Similarly, for Indian village adults, there seems to be a greater continuity of genres and games from childhood.

Folklore